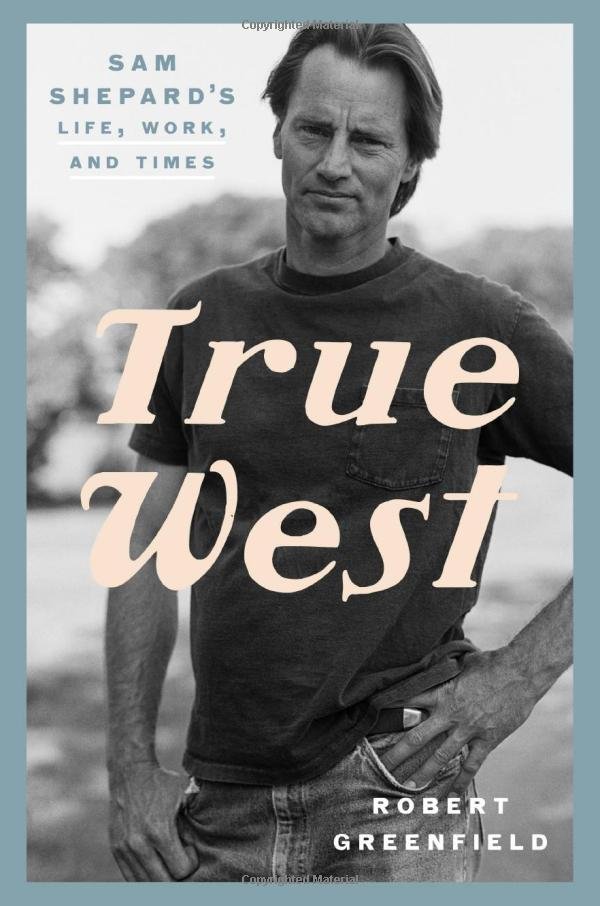

True West: Sam Shepard’s Life, Work, and Times

—Jan Farrington

True West: Sam Shepard’s Life, Work, and Times by Robert Greenfield (Crown, 2023)

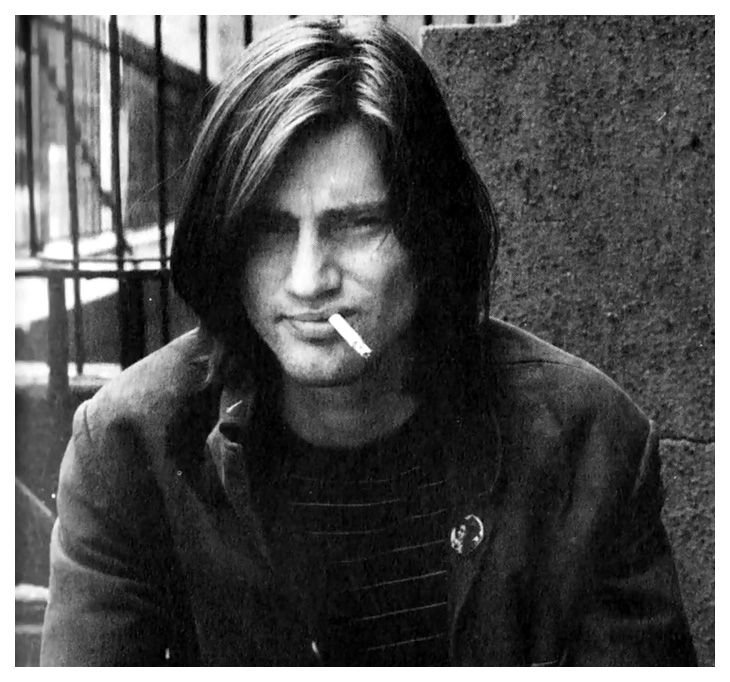

It’s a given, probably, that few readers would pick up a bio of playwright, actor, writer, movie heartthrob, and sometime rock ‘n roller Sam Shepard unless they already had an interest in the man. Of course, I’d pick it up just to gaze at the pictures of the young Sam—but that’s how shallow I am. (A London observer in the early days sighed it was like seeing a sexy mashup of “Henry Fonda and Gary Cooper” mosey into a room.)

The thing is, Robert Greenfield’s excellent book True West isn’t going to do what you want—namely, untangle the puzzle of Sam Shepard. Greenfield gives us the pieces (an exceptional collection of them, in fact) and guesses about what they mean—but in the end, Shepard remains mysterious.

He’d like that. Outside his writing, staying a mystery man was what he worked at the hardest.

Born during WWII while his father was in the Army Air Force, Shephard’s parents became respected California school teachers (already, you’re saying “What?”) in and near Pasadena, Greenfield writes, “in exclusive high schools whose entire student bodies were composed of children of wealthy families.” Sam (whose family called him “Steve” for a long time) and his siblings grew up in a nearby (and less expensive) small town, whose vibe was an odd mix of Western outlaw spirit and American Graffiti. In time, says Greenfield, that world “permeated his work, enabling him to present a vision of American life that had never before been seen onstage.”

Home was not heaven. Like many returned veterans, his father Sam Rogers was a troubled alcoholic. Over time he became ever more depressed, erratic, and abusive toward his wife and family. Eventually he abandoned them and became a wanderer, still drifting by at times. (Shepards’s father lived until 1984; by that time, his son’s theater career was well underway, and their encounters were a major element of the stage plays.) While he was growing up, Sam’s mother was often given the use of cabins and vacations homes by parents at her school: Sam lived on the edges of the American Dream, but remained an outsider.

Acting was Sam’s ticket out of California. In 1963 he joined a small touring company that eventually landed him in New York, where he roomed with best friend Charles Mingus III (yes, the jazz legend’s son, a high school buddy) and bussed tables at The Village Gate, where he mingled with jazz and off-off-Broadway theater people. (The head waiter at “The Gate” founded an experimental theater company, and produced two early Shepard plays in 1964.)

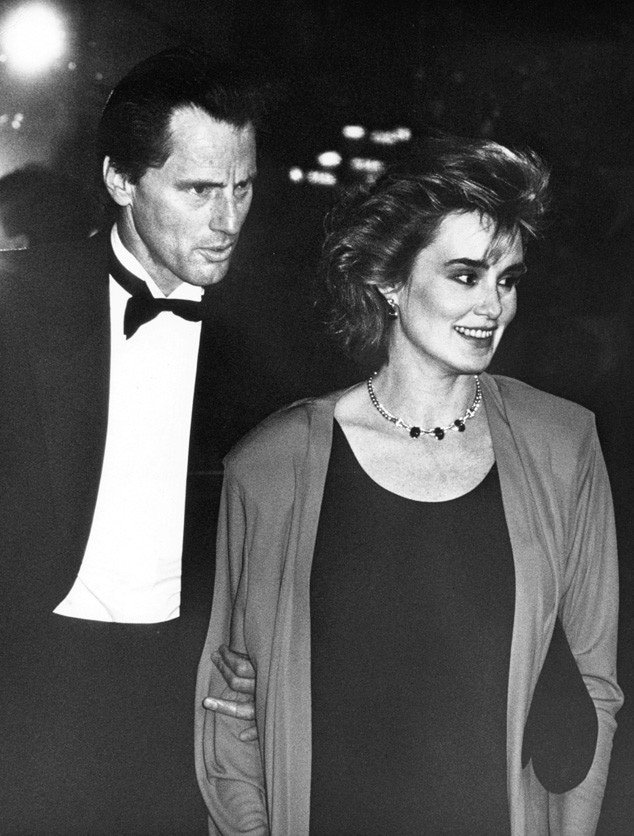

Over and again in the bio, one has the feeling the young Shepard might have been the luckiest SOB in modern American playwriting. Yes, he worked hard at his writing, but thousands do. Somehow, he was often in the right place, met the right people—and the combination of his magnetic looks and real talent created opportunities that didn’t materialize for most NYC theater wannabees. He worked with the downtown theater La MaMa on several early plays; began a family with a young actress, O-Lan Johnson; took them to London to work with the Royal Court Theatre; moved back to the U.S. and bounced among homes for decades: Marin County (California), Minnesota, Kentucky, New York and more—working in New York and West Coast theater all the while. Early on, he fell in love with poet/singer Patti Smith (they wrote the 1971 play Cowboy Mouth together), and later with actress Jessica Lange. He and Lange had children and lived together for thirty years, two people with surprisingly tough backgrounds, trying to make things work.

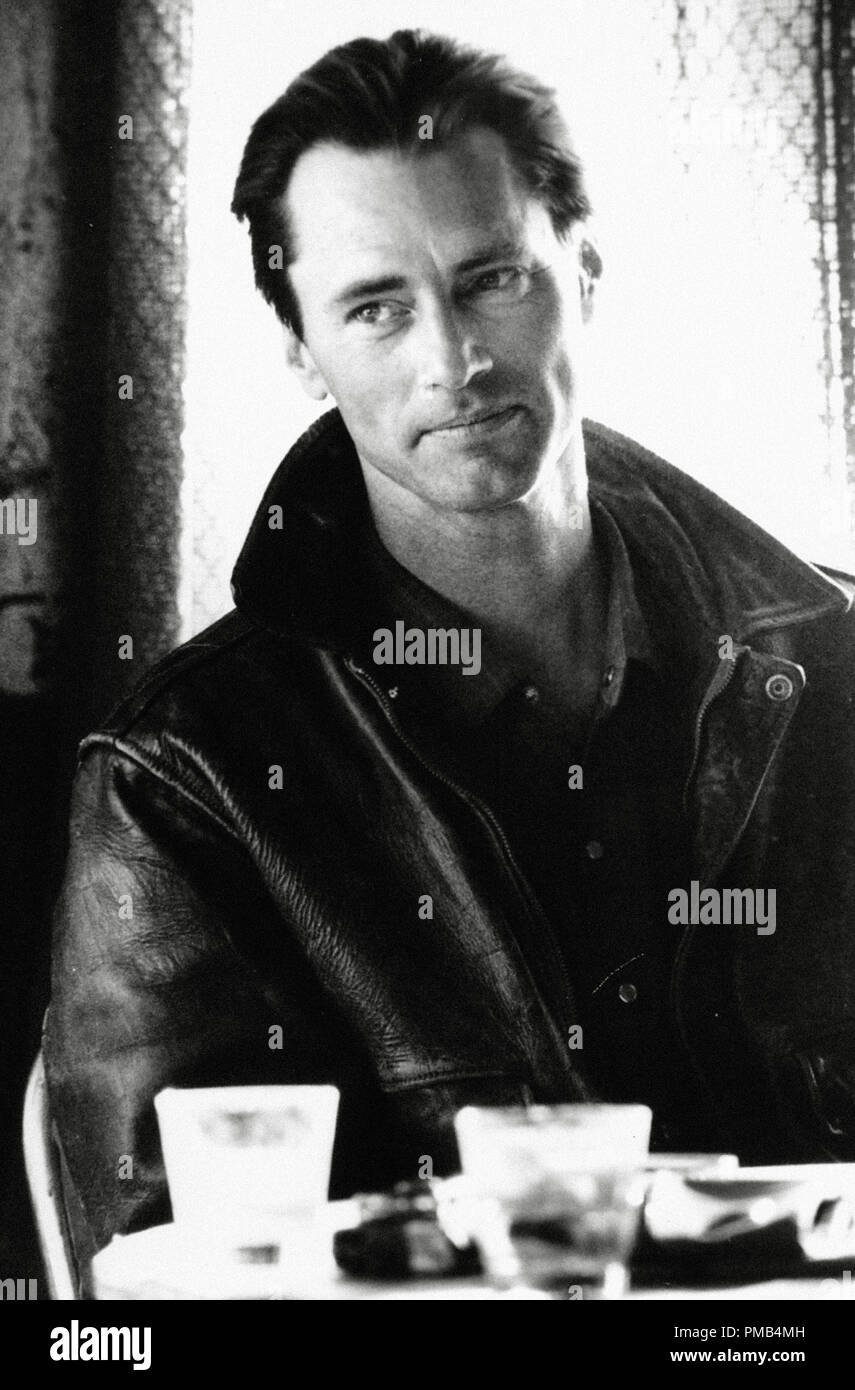

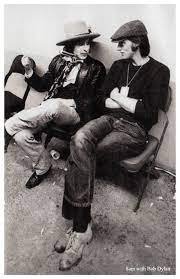

Sam starred in a string of movies (The Right Stuff and Paris, Texas among them). He said they paid the bills for the horses he loved raising. He played in a band called the Holy Modal Rounders, and toured with Dylan—quite a story in itself.

Shepard’s plays—the sources, the writing, productions, casting, hits and misses—are all handled in fascinating detail. Somehow, working the same stony ground of the millions of American families living small, hard lives, missing out on the “Dream” version of the nation, Shepard kept finding new things to say—sad, funny, bitter, prescient—in Curse of the Starving Class and Buried Child (1978), A Fool for Love (1983), A Lie of the Mind (1985), and above all, perhaps, the iconic True West (1980). Not the happiest portrait of ourselves—but dark, true, and compelling all the same.

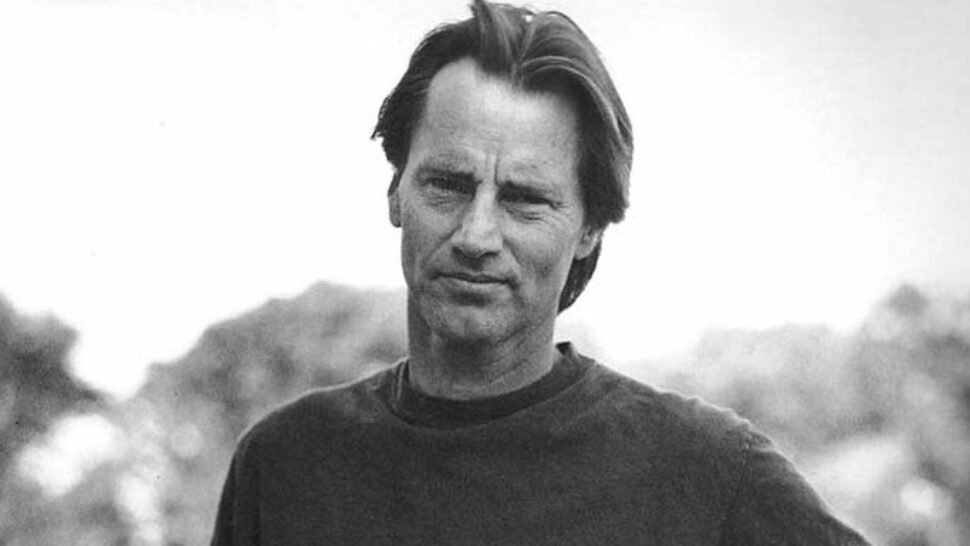

Sound like your cup of tequila, worm and all? True West is an honestly researched and very well-told life story about one of our most important modern American playwrights, the charismatic, sociable, reclusive, prickly, self-doubting, egotistical—and always mysterious—Sam Shepard.

In a New Yorker piece after he died in 2017, Patti Smith described Sam in terms that are as American as they come: Sam liked being on the move. He’d throw a fishing rod or an old acoustic guitar in the back seat of his truck, maybe take a dog, but for sure a notebook, and a pen, and a pile of books. He liked packing up and leaving just like that, going west.