Alan Lake Factori(e) @ TITAS/DANCE UNBOUND

—Teresa Marrero

A revolutionary and historic painting on display at the Louvre in Paris may not be the usual subject matter to inspire a contemporary, multi-disciplinary dance performance. However, the Québec-based company Alan Lake Factori[e] accomplishes just that with their 65-minute piece Le cri des Méduses (The Raft of the Medusa). Presented in association with AT&T Performing Arts Center as part of the new TITAS /DANCE UNBOUND’s “Unfiltered” series, it showcases a work that, as TITAS’ own material states, “both promises and delivers a startling artistic shock.” The Dallas performances on March 17 & 18 marked the company’s U.S. debut.

The Medusa of the title refers to the ill-fated French frigate Méduse and not the mythical figure. By historical accounts, the ship was run aground off the Northwest African coast in 1816, due to the incompetence of a politically-appointed, inexperienced captain. The ship carried 400 people; there were lifeboats for 250. The crew and first-class passengers were afforded the privilege of survival in the boats, while the rest—146 men and one woman—were loaded onto a makeshift raft, half of which quickly sank upon launching into the turbulent seas.

After thirteen days adrift only 15 souls were on the raft when rescue came. Survival included the need to cannibalize the bodies of the dead. While historic paintings up to then had focused on noble or heroic acts in the tradition of epic poetry, French Romantic painter Théodore Géricault revolutionized this tradition by depicting the human condition in all its duality of baseness and beauty. His large-scale oil painting (approximately 16 by 23 feet, and completed within two years of the disaster) Le cri des Méduses has become an iconic image both of political decrepitude and the indomitable human will to survive.

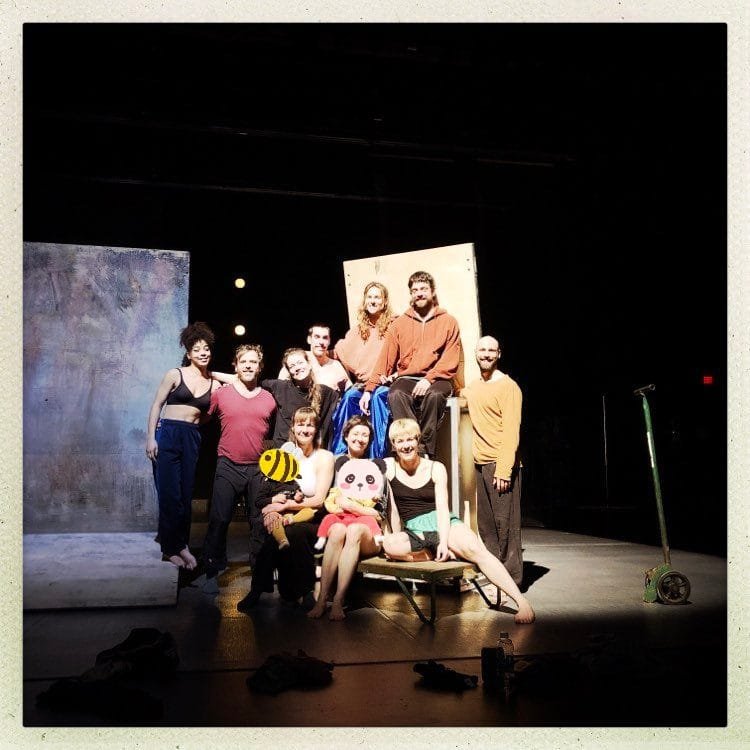

After much time contemplating this famous painting, the Alan Lake company (Lake himself is a painter and visual artist as well as dancer) collectively devised this extraordinary dance piece (choreography by Lake in collaboration with the original cast members). Performers in Dallas were: Kimberly De Jong, Geneviève Robitaille, Josiane Bernier, Esther Rousseau Morin, Jo Lainy Trozzo Mounet, Odile Amélie Peters, Alan Lake, Danny Morissette, and Sacha Ouellette Deguire. Not a weak link among them, they had the Moody Performance Hall audience on its feet with a well-deserved standing ovation.

At the center of the action is a tripartite wall-like structure with nine visible panels. From this approximately 12-foot tall structure, the dancers maneuvered with gravity-defying artistry. They climbed up it, as though scaling a smooth granite mountainside; they hung off it, seemingly in a feat of sheer will. This structure afforded height and depth to the dancers’ possibilities, expanding the audience’s visual field upwards, and augmenting the almost imperceptible magic of nine bodies moving through space and in harmony with each other.

A stroke of genius was designing a ‘raft’ that was not horizontal, but vertical, serving also as a canvas to color and contour the dancers’ bodies. At several points, literal painting took place as one dancer hosed paint directly onto the bodies of others. While the action began with the dancers dressed in contemporary street clothes (jeans, T shirts), eventually some, but not all, pared down to their underwear, and later into nakedness. The nudity became integral to the action, and in no way sexualized or fetishized the bodies of either men or women. Apparently, nudity was the issue that made this piece part of the UNFILTERED series, one that lets audiences know the performance contains elements that may offend some sensibilities.

In the talk-back following the performance, an audience member commented on the strength of the six female dancers, whose physicality matched the three males. Equality, they replied, is a core value of the company. Indeed, it was refreshing to see the lack of male/female dichotomy often seen in dance and elsewhere. I was particularly struck by a particular move: one of the tallest male dancers jumped off the ground and straddled an equally tall female counterpart’s shoulder. Yes, the shoulder. Unaided by others. This is only one instance of the athleticism and strength of the Alan Lake dancers, along with an extraordinary physical vocabulary that goes beyond established modern dance techniques. Their athleticism was accompanied by a fluidity that remained constant throughout this demanding performance—offering the extraordinary sensation of movement at sea without being at all literal.

Another mention from the talkback was the fact that the company’s female dancers continue dancing through and after pregnancies. Childbirth is considered a normal life event, and not an impediment for women.

Original live music by composer Antoine Berthiaume cast a sometimes disturbing, sometimes hypnotic spell that complemented the lighting design by Karine Gauthier. True to the Géricault painting’s dark color palette (a deep ochre, browns, blacks), the lighting followed this schema. The stage framed fog and darkness to begin with, subsequently alternating with sudden light changes. A particularly effective trope is the backlighting upstage by rows of huge yellow lights, vertically placed. Another effective staging device was a series of tall, hanging, transparent curtains that gave the impression of moving water—but with movement coming from the top down, rather than the usual representation of water on stage through various azure colored, horizontally flowing long cloths.

Devised by the original ensemble over the course of several years, the dancers mentioned in the talkback that each of them had an expressive, physical voice in the creation of this piece. While improvisation was at the heart of the initial process, the final result is scripted and set, even though at times it gave the impression of being improvised. And, while there is not a discernible storyline (after all, they are riffing off a visual image), I noted that at some point there seemed to be a sort of invisible narrative or conversation among the dancers that we, the audience were not privy to. I did pose this observation during the talkback and was assured that indeed, the dancers had an internal vocabulary attached to various segments of the dance.

In the painting by Géricault, the viewer is close to the action: the people in the raft are seen up close, falling off into the sea. In the choreography, several of the dance sequences develop downstage (close to the theatre audience), creating an equal intimacy between subjects and the viewers. The audience is invited to step into the tragedy, to become emotionally involved. While constantly in motion, there are moments of tableaux-like stillness that pause long enough (though the dancers never stopped moving entirelly) for us to feel the desperation of the people adrift.

Thanks to Charles Santos, TITAS Executive/Artistic Director, for the bold programming of this new series, which exposes Dallas audiences to world-class performances regardless of (possible) constraints unrelated to the art itself.

Teresa Marrero is Professor of Latin American and Latiné Theater in the Spanish Department at the University of North Texas. She is also an avid Argentine tango dancer who has had the privilege of seeing ground-breaking performances such as Pina Bauch´s Bluebeard´s Castle to Béla Bartók´s score, as well as classic ballet performances by Rudolf Nureyev, Margot Fonteyn, and Mikhail Barishnikov.