‘Evolution’ @ Chamber Music Society of Fort Worth

—Gregory Sullivan Isaacs

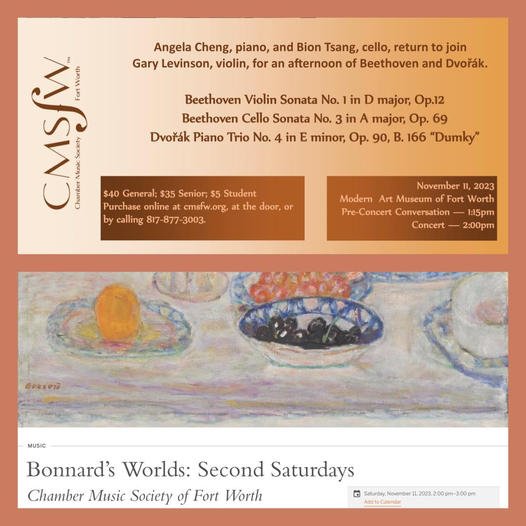

On Saturday, November 11, 2023, the Chamber Music Society of Fort Worth presented a concert titled “Evolution”—although it was somewhat murky as to how that related to the program. We heard Beethoven’s “early period” Violin Sonata No. 1 in D major, Op.12 as well as his “middle period” Cello Sonata No. 3 in A major, Op. 69. The program concluded with a 90-year forward leap of place and time, via Dvořák’s Piano Trio No. 4 in E minor, Op. 90, B. 166, subtitled the “Dumky.” This piece also presented a dramatic move away from formal Haydn-esque classicism to a much looser construction inspired by Czech folk music.

As is usual with CMSFW presentations, this concert featured world-class artists. We heard pianist Angela Cheng, cellist Bion Tsang, and violinist Gary Levinson, who is also the society’s artist director. The venue adds significantly to the experience: the auditorium of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth combines simple elegance with superb acoustics. Each of the players has a distinguished biography full of important teachers and worldwide concert appearances. The first-class performance we heard on Saturday certainly validated all of the program's quoted laudatory review excerpts and impressive biographical details.

First up was Beethoven’s early violin sonata (No. 1 in D major, Op.12) with Levinson and Cheng doing the honors. This was a very clean and historically accurate performance of the Beethoven; he was at the time very much under the influence of his teacher Haydn. Of special notice was Levinson’s minimal use of vibrato, a subject of much musicological debate about the performance practices of the era. He managed to straddle the line between “none” and full romantic throbbing.

Beethoven’s cello sonata, which followed, marked a stylistic change in the composer’s approach to sonatas. (Maybe this is part of the "evolution” referenced in the concert's title.)

As opposed to the early violin sonata we heard, Beethoven employed the two instrumentalists much more as equal partners; the music is replete with interactions that the earlier work lacks.

Both cellist Tsang and pianist Cheng took full advantage of Beethoven’s intentions and brought out all of the collaborative elements that paper the score. Tsang’s sound is not as assertive as Levinson’s on his brash Stradivarius, and (along with Tsang’s lower position seated on floor level) he sounded slightly muted or remote.

Adding to this acoustical anomaly, Cheng was frequently on the louder side of proper balance. Part of this effect was due to the fact that the top of the very grand Steinway was opened to full mast for the entire performance. While this position was well suited for the romantic antics in the Dvořák trio, it was too outspoken (“present”) for both of the Beethoven pieces. They would have benefited from using the smaller lid prop, and from Cheng taking a somewhat subtler approach. However, there was much to admire in her performance. Her playing was remarkably clean due in part to her impeccable technique, but also from her judicious use of the sustaining pedal.

An aside: Beethoven was writing for a very different instrument than the magnificent specimen on the art museum’s stage. This earlier instrument was called the fortepiano (or pianoforte) because unlike any of its predecessors, such as the harpsichord, the revolutionary pianoforte could play both piano (Italian for soft) and forte (Italian for loud). This is because the string was hit with a touch-sensitive and levered hammer, giving the player a dynamic range depending on the force used on the key. The mechanism on the harpsichord only plucked the string, rather like using a guitar pick. No wonder composers quickly ditched the mono-dynamic (and thus less expressive) older instrument for the greater nuance of the “high tech” piano.

While Beethoven’s early fortepiano was a subtle instrument that quickly evolved, contemporary performances on the modern version should keep the instrument’s later technical advancements in mind, and back off somewhat from its full dynamic capabilities.

After intermission, the players left classicism far behind and opened up stylistically, delivering a terrific performance of Dvořák’s unusually constructed trio. Even Cheng’s full-up-piano-lid position was more at home here.

The word dumka (singular of dumky) comes from the 16th-century Ukrainian/Slavic social tradition of storytelling. A group of friends, we assume, would sit around with a pitcher of beneficial beverages and tell tall tales for the evening’s entertainment. The stories could be heroic or tragic, happy or sad, lamenting or celebratory, true or otherwise, and occasionally exaggerated (or at least embellished). Although the melodies in this present work are certainly folk-influenced, the dumky in Dvořák’s trio are all original takes on the style. Further, the composer defined his dumka as having two contrasting elements (wild/sad, for example), giving him a wealth of differences to draw on in creating the music.

The form of this work can be seen as a series of musical ideas grouped into more traditional movements, but that really is a technical triviality. In the hands of this creative trio of players, each dumka was markedly different—and one led to the other, as though offered by different folks around the same table. We, the audience, were thus freed to make up our own fantastical narratives as each one musically unfurled. Since this work immediately followed the composition of the composer’s Requiem (1890), we can proffer that the composer might have wanted to lighten the mood with his next work.

The balance and interactions between the players were excellent as each player chimed in with more details of each dumka. The presentation, while grand, could have benefitted from the players having more fun along the way. It was all too serioso—perhaps partially explained by the absence of the “beneficial beverages” in the pitcher mentioned earlier as a dumka must-have. Who knows?

WHEN: November 11, 2023

WHERE: Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

WEB: cmsfw.org (Upcoming: “No Barriers”—Orion Weiss, piano, Gary Levinson & Michael Klotz, violin, Ani Aznavoorian, cello—January 6, 2024)