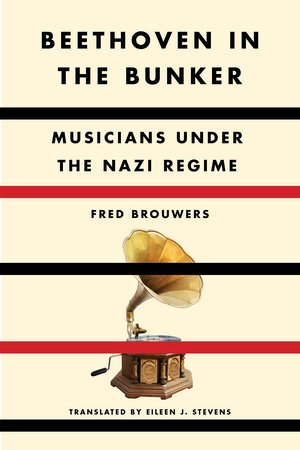

Beethoven in the Bunker

—Cathy Ritchie

Beethoven In The Bunker: Musicians Under The Nazi Regime

By Fred Brouwers (translated from the Dutch by Eileen J. Stevens)

Other Press, 2023. Originally published 2019.

This book’s head-turning title caught my eye across a crowded room of library shelves. While its narrative quality ebbs and flows at times, its unique subject matter carries the day.

In his useful Introduction, classical music connoisseur/presenter Fred Brouwers reveals, among other tidbits, that while we probably all know Hitler liked his Richard Wagner, Anton Bruckner, and Ludwig von Beethoven, he also loved opera. After his death, the contents of his legendary hidden bunker revealed some 78 rpm surprises: recordings from banned and so-called “despicable” Jewish and Russian composers, including Felix Mendelssohn, Jacques Offenbach, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Alexander Borodin. Compounding the surprise, some of the recordings featured performances by Jewish musicians.

As Brouwers puts it, better than I could: “Hitler had fallen under the spell of the music and the talent of particular performers to such an extent that he forgot they were the enemy. This has led some historians to suggest he was not such a bad fellow, really. In this, however, they are overlooking the death toll….While Hitler sat secretly enjoying previously recorded forbidden music in his bunker, musicians made of flesh and blood were denied a means of making a living. They died in concentration camps or in other war-related circumstances….All of which makes this an extraordinarily fascinating chapter in music history.”

Brouwers devotes the rest of his text (which includes a bibliography and “bunker playlist”) to lifting up the lives of the bunker’s “select” group of performers and composers, describing their influence and life circumstances during the Third Reich.

Some of their names are immediately recognizable—Arturo Toscanini, Richard Strauss, Igor Stravinsky, Paul Hindemith, Herbert von Karajan—while others may be only vaguely familiar or unknown. (Unfortunately, only two women are included, both seemingly obscure: Elly Ney, a “fervently” anti-Semitic concert pianist; and Anita Lasker, a “little-known but noble” cellist.) Some pages are devoted to each individual musician; and this is where I encountered the elements that made this book an up-and-down reading experience for me.

Perhaps the fact that the text originally appeared in Dutch and was later translated into English is partially to blame. I found some of Brouwers’s prose by turns vague, meandering, and then suddenly sardonic for no clear reason. He offers the standard biographical background for each person, but sometimes seems to embrace tangents not relative to Hitler or the Nazis. His chapter on Herbert Von Karajan impressed me as the most cohesive of the lot, telling the conductor’s story clearly. While I did definitely glean new knowledge about these talented and, in many cases, unfortunate people, on the whole I periodically felt myself floating from subtopic to subtopic with no unifying rope to pull me through.

However…..Brouwers’s topic is fascinating and important, one that deserves exploration by anyone willing to tackle the book, translation issues notwithstanding. Despite my caveats, I recommend this Beethoven in the Bunker to music aficionados and cultural historians alike. These often brave, upstanding artists merit recognition wherever it materializes.