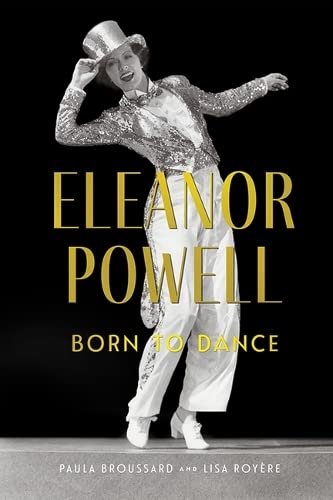

‘Eleanor Powell: Born to Dance’

—Cathy Ritchie

As a biography nerd, I carry a mental bucket list of famous folks about whom I hope to learn more someday. That list is now one name shorter. Thanks to a fine book by Paula Broussard and Lisa Royere (University Press of Kentucky, 2023), I’ve become better acquainted with performing artist extraordinaire Eleanor Powell (1912-1982), who was absolutely—as the book subtitle says—Born To Dance.

No less a terpsichorean than Fred Astaire often proclaimed that Eleanor Powell was not only the finest female tap dancer anywhere, but actually THE best tapper of all time, regardless of gender. Her talent and creativity became mainstays of popular entertainment in the 1930s and beyond.

Powell was a native of Springfield, Massachusetts, born in 1912. Her single mother Blanche introduced Eleanor to dance lessons at age 11. The athletic girl first studied ballet and acrobatics. Powell’s aptitude for dance was immediately apparent, and during her teenage years she performed frequently in the Atlantic City area. During one of her gigs, she was spotted by Eddie Cantor and Jack Benny, who suggested she tackle Broadway. She and Blanche moved to New York City in 1927.

Powell soon realized that tap dancing was the ticket to making a living on Broadway, though she initially disliked the instruction she received. But fortunately for us all, Powell recalled that “In the seventh lesson, it all came together.” At age 16, she joined the vaudeville circuit and crossed paths with tap dance master John “Bubbles” Sublett and her eventual lifelong friend and mentor, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.

Powell’s style ultimately fused her ballet and acrobatic training with what could be described as “grounded taps” style. She would barely leave the floor, but alternated her steps with high-flying leaps and grandes battements. At age 17 Powell was on Broadway, starring in numerous revues and musicals. Even in those early days, critics labeled her “the world’s greatest female tap dancer.” Next came Hollywood.

After a few false starts, Powell was signed by MGM. By the mid-1930s, she was arguably the studio’s greatest musical star. Her series of Broadway Melody films—1936, 1938, and 1940—not only wowed audiences but saved MGM from financial ruin. Her leading men included Robert Taylor, Fred Astaire, James Stewart, George Murphy, and Robert Young. Perhaps most significantly, Powell was her own choreographer; throughout her career, she displayed great originality, creating jaw-dropping tap sequences using all varieties of props and backgrounds—including a dancing dog she trained herself.

Unfortunately, though she took lessons for many years, Powell’s acting ability and singing voice were not nearly as amazing as her dancing. (Her vocalizing was frequently dubbed.) However, as per her perfectionist personality and devotion to her craft, Powell strove to conquer all areas of filmmaking, and her later-year non-dancing moments became stronger. Her other films included Rosalie, Lady Be Good, Ship Ahoy and I Dood It. She once described herself as MGM’s “dancing workhorse.”

Fred Astaire was actually nervous about performing with Powell in Broadway Melody of 1940, as he was concerned about their nearly identical heights and the overall power of her taps. However, their duo to “Begin the Beguine” by Cole Porter has since been ranked one of the greatest tap sequences ever filmed. As a layperson, I must agree: it’s three minutes of dance heaven. Prepare to be dazzled:

For years Powell focused on her art and career, feeling no immediate need to marry, though she did hope to someday be a wife and mother. (At one point, a columnist labeled her Hollywood’s “old maid.”) But in 1943 after a six-month courtship, Powell wed actor Glenn Ford, giving birth to her only child Peter in 1944. She continued making films during this time, though she was often plagued with injuries and illnesses necessitating long absences from the soundstages.

Spoiler alert: Glenn Ford fans may find portions of this book tough sledding, as he proved to be a largely indifferent father and cheated on Powell with women and men. Powell did her best to portray their marriage as successful, but they divorced in 1959.

As tap dancing gradually fell out of public favor in the postwar years, Powell was given smaller dancing roles in films and less than star billing, though she continued to innovatively choreograph at least one number per movie. But as her film output wound down, new opportunities arose.

During the 1950s, she hosted a children’s Sunday-School program on Los Angeles television, eventually winning multiple local Emmy Awards for her appearances. In later years, Powell ventured into night club work, regularly receiving heartfelt reactions from her audiences, who fondly remembered her glory days at MGM. By all accounts, her athleticism never wavered as she grew older. Her final public appearance came in 1981 during a televised tribute to Fred Astaire, at which she received a standing ovation. Powell died of ovarian cancer in 1982 at age 69.

Powell was not only admired for her film accomplishments, but also for her personal generosity. She always bonded with her film crews, and corresponded with numerous fans and colleagues over many decades. Powell was also ahead of her time vis-à-vis race relations; she had a deep friendship with Bill Robinson, and was noted for her efforts to include persons of color as backstage workers and dancers in her production numbers.

While Broussard’s and Royere’s descriptions of Powell’s dance numbers and choreographic creations are detailed and vivid, there’s no substitute for seeing her in action. Fortunately, Powell footage abounds. Her major films are all available on DVD, including a multi-disc collection of her three Broadway Melody movies. There are documentaries and interviews, and individual dance segments are easy to find on YouTube, as noted above.

Eleanor Powell brought happiness and high-quality entertainment to the masses, as conveying the joy of dance to one and all was always her ultimate goal. This book is a long-overdue yet welcome tribute to one of the greatest artists of our time, and a great lady to boot.