‘Quartet: How Four Women Changed the Musical World’

—Cathy Ritchie

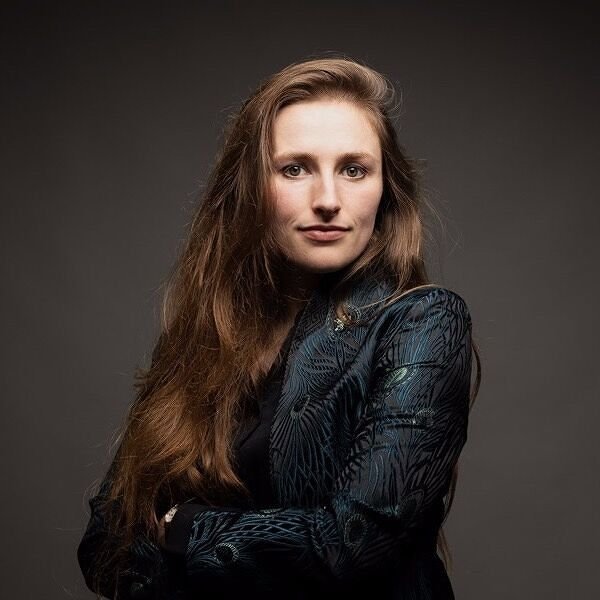

Quartet: How Four Women Changed the Musical World

Leah Broad (Faber & Faber, 2023)

In 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, future President John, as he and other Founding Fathers-to-be met in Philadelphia for a Second Continental Congress: “Remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors….Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could.”

When it comes to the 21st-century world of British female composer/performers, we have Oxford music historian Leah Broad to thank for helping us “remember” a few remarkable women, some 300 years post-Abigail. In her multi-pronged biography Quartet, she brings us four tales of dedication, hardship, chronic discouragement, and occasional triumph. Yet each of these true-life tales is enlightening.

Since her subjects’ lives overlapped each other to varying degrees, Broad’s approach is to blend their stories together, shifting her narrative focus back and forth among them. This is helpful in terms of appreciating what parallel lives the women led, but can occasionally be a bit confusing to readers. So here’s a summary look at the individual artists.

Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944). Arguably the best known musician of the quartet, Smyth was also notable for her outgoing and at times bombastic personality; her varied interests, including women’s suffrage and social justice; and her frequently complicated same-sex private life. Objects of her nearly obsessive affection included author Virginia Woolf, though the latter apparently did not return her feelings in kind beyond friendship.

Smyth’s musical output was varied as well, ultimately including songs, pieces for piano, operas, choral works, and both orchestral and chamber music. Smyth was the first female composer to become a Dame, though her achievements were continually marginalized throughout her career. Among her many compositions were the Concerto for Violin, Horn, and Orchestra, and the Mass in D. Her most famous opera, The Wreckers, premiered in 1906 and was considered at the time to be the most important British opera to appear between the eras of Henry Purcell and Benjamin Britten. Another Smyth opera, Der Wald, premiering in 1903, was until 2016 the only such work by a woman composer to be mounted by the Metropolitan Opera.

These instances of success notwithstanding, Smyth’s career was nevertheless one of struggle, as she fought for recognition and respect from the virtually all-male British musical establishment. She shared this chronic state of being with the other quartet members.

In honor of her 75th birthday in 1934, Smyth was feted via a festival in Royal Albert Hall with the Queen in attendance, though Smyth was totally deaf at this point, rendering the occasion literally and figuratively a muted one for her. Her final major work was the one-hour “vocal symphony” The Prison, debuting in 1931. She also wrote several volumes of lively autobiography before her death in 1944.

Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979). Clarke not only composed but was a viola virtuoso as well, becoming one of the first female professional orchestra members in Britain. Her performing talents were in demand by conductors throughout her life.

In 1916, she relocated permanently in America. While her compositional output was not especially large, and many of her works’ scores were never published in her lifetime, recent decades have witnessed a resurgence of interest in her life story and accomplishments, including the formation of the Rebecca Clarke Society to further her music’s “study and performance”.

Clarke’s creations included songs, compositions for viola and piano, choral music, and “tone poems,” among others. Her long, happy marriage to pianist and fellow composer James Friskin perhaps slowed both her output and performance schedule a bit, and she may have also suffered from depression, as she dealt with frustration imposed by the overwhelmingly male classical establishment. But before her death in 1979, Clarke resumed offering viola performances in New York City, in alignment with the 1970s resurgence of interest in women composers.

Dorothy Howell (1898-1982). Howell was a pianist who also displayed compositional variety. Arguably, her most famous work was the “symphonic poem” Lamia, based on the poem by Keats; it premiered at “The Proms” in 1919.

Her numerous other works included pieces for full orchestra plus piano and violin. Her last-known orchestral work, Three Divertissements, received its premiere in 1950. Howell taught at Britain’s Royal Academy of Music for many years, and continued private work with students after her retirement. She died in 1982 at age 83.

Doreen Carwithen (1922-2003). Carwithen was the youngest of Broad’s composer quartet, but her path did cross with several of the others as she studied piano, violin and cello.

Her compositions included concertos, songs, overtures, string quartets and sonatas. But Carwithen would discover her true niche in music for the cinema: she composed scores for over 30 British films along with the documentary of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation.

Her output was likely somewhat affected by the circumstances of her private life: for several decades, she was involved in an affair with fellow composer William Alwyn, a married father, until finally becoming his second wife in 1975. Much of her time and energies were devoted to furthering his career and thereby reducing her own to a degree. But Carwithen’s centenary was marked with a festival in 2022, and she has been recognized by the BBC and others for her achievements.

These four women’s careers and achievements may have differed, but Broad consistently reminds readers that the one bond shared by the ladies was their constant struggle for recognition and public/monetary success. Works by women composers were simply not taken as seriously as those of their male counterparts, a situation that may still persist today.

Along the way in her narrative, Broad offers brief analyses of many of her subjects’ compositions, and includes a five-page discography of those pieces’ recordings.

This book is required reading for students of women’s history, and for those pursuing musical careers. Broad offers well-crafted prose that keeps her multiple “plots” moving briskly, emphasizing these women’s hard times and successes, along with their lifelong dedication to classical music. Broad’s fine group biography—she does indeed “remember the ladies”— is a major wake-up call for all of us.