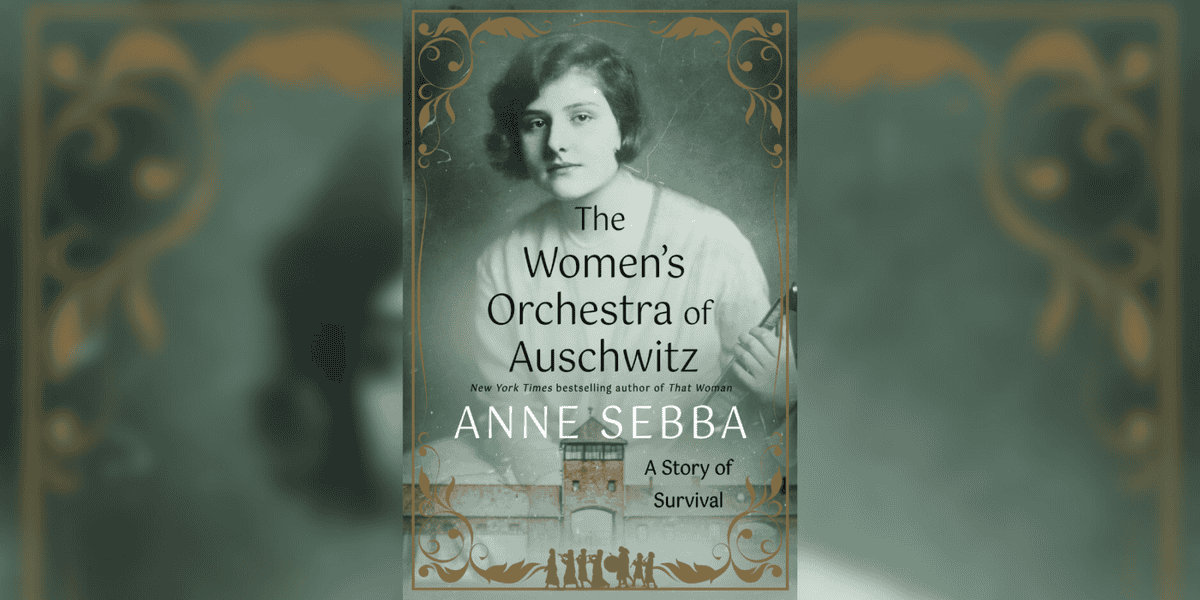

‘The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz: A Story of Survival’ by Anne Sebba

—Cathy Ritchie

In 1980, I joined a large contingent of America's television viewing population in watching one of the most controversial films ever to air on the small screen: Playing For Time, based on the 1976 memoir by Holocaust survivor Fania Fenelon. The book described her years of Auschwitz imprisonment, during which she played in a women's orchestra that performed for their SS captors.

With a teleplay by Arthur Miller, the film starred Vanessa Redgrave as Fenelon. The emotional true story drew viewers, but the program also sparked controversy because of Redgrave’s political activism. Fenelon herself had balked at the casting, as the 6-foot-tall Redgrave bore no physical resemblance to the less than 5-foot-tall author. Nevertheless, the film won a Peabody Award and Redgrave an Emmy as Best Actress.

While the notion of an orchestra consisting of prisoner/performers seemed incredible to many, the musicians’ existence was just another perverse aspect of concentration camp life. Amazingly enough, many in the Nazi upper hierarchy were confirmed music lovers, among them Josef Mengele, Heinrich Himmler, and Adolph Hitler himself.

Along with Sunday concerts, orchestras provided accompaniment during back-breaking work details, for groups of prisoners marching from one location to another—and perhaps most horrifically, music for "greeting" newly-arriving human transports as they alighted from their cattle cars.

Thankfully, some musicians survived their ordeal, and wrote memoirs of the experience. Author Anne Sebba brings these women to life by turning their words into gripping narrative in The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz: A Story of Survival (St. Martin’s Press 2025).

The all-female group's members ranged from teenagers with only a few previous music lessons to a handful of seasoned professionals. Thus, early on, the group's level of musicianship was erratic and amateurish. But all that changed with the arrival of prisoner Alma Rose, a virtuoso violinist and niece of Gustav Mahler, vividly portrayed in Playing For Time by Jane Alexander, who won the Emmy for Best Supporting actress for her portrayal.

The "formidable" Rose, who was "charged with making something out of sheer rock," according to one survivor, affected change in both the orchestra as a whole—n particular, requiring lengthier and more frequent rehearsals, increasing the group from 20 players to 40, and pushing to improve members' personal situations, including new "privileges and comforts."

Above all, Rose "made something beautiful to listen to," though she was always demanding and often overbearing. Rose recruited the best musicians available from arriving transports, and also sought out top-quality instruments. She "stood up to the SS" and generally won her battles, as the camp's higher-ups sincerely desired a quality orchestra.. Through her influence, Rose was able to save the lives of numerous Jewish women instrumentalists.

Rose rarely made an effort to become close to any of her musicians, but still inspired strong loyalty from most. Along the way she was forced to handle political skirmishes among her performers stemming from their varied backgrounds and religions. Somehow, she succeeded in maintaining cohesion.

The music itself was a source of discontent. As one survivor later asked rhetorically: "How could we play light music here, against the background of the flames and black smoke that billowed day and night from the crematoria chimneys? Yet Alma consistently and firmly inculcated in us...the orchestra means life. It survives together or dies together. There is no halfway road."

As for the ever-present crematoria, one survivor commented: "We played DURING a selection [of prisoners who would be sent to die immediately, or allowed to live on for a time] but not FOR a selection. It's easy to misunderstand....We had to play. We did it as a job." Having to perform for the Germans at all was an ongoing moral agony for the musicians, but as many made clear in later years, they had no choice if they wanted to live.

The arrival of Fania Fenelon brought a new spark to the orchestra. As Fenelon was a professional singer, Alma Rose was able to stage operetta selections for eager SS audiences. And personally, Fenelon brought sophistication and charm into the women's dreary existence, along with fortune telling upon request.

By early 1944, Rose was clearly feeling the stress behind her circumstances. The musicians noticed how physically and emotionally drained she was becoming. Then Rose was informed she was "to be released from the camp to play outside" for an event. She happily attended a birthday dinner one evening, but became ill upon her return. The camp doctors were consulted to no avail. Alma Rose died on April 5, 1944, age 37.

Could it have been accidental food poisoning, or something more deliberate? Doctors' tests were “inconclusive,” and to this day the cause of Alma Rose’s death is unknown.

According to Sebba, surviving orchestra members posthumously characterized Rose as akin to a sabra, "a thorny cactus on the outside but inside, a refreshingly sweet fruit”—and concludes that she "literally and courageously embraced the life-giving force of music; without her, survival for all of them would have been thrown into doubt."

Alma Rose's successor was a Polish pianist who proved a total failure as a conductor. In any case, the SS reduced the group's repertoire and performing schedule to the point that "there was no search for perfection" such as had existed under Rose. Several months later, D-Day arrived, with a faint hope of rescue by Allied forces…if only they would come in time.

The orchestra suffered greatly without Rose. At one frightening point, all the group’s Jewish musicians were shipped to Belsen and forced to endure horrific living conditions. Before liberation by the Allies, and when told they would play no more music, the women had to find strength and survival within themselves.

Sebba devotes her final chapters and a lengthy epilogue to the orchestra members' fates in the post-war world. As she summarizes, "The suffering for those who had lived through the daily horrors of a concentration camp did not end with 'liberation' ." Some of the survivors wrote autobiographies, and most married and raised families. Fania Fenelon's "fictionalized" book particularly outraged many of the surviving musicians because of her unflattering portrayals of Alma Rose and others. Some orchestra members participated in documentaries and gave interviews, including several with author Sebba. All carried scars and memories, as indelible as the numbers on their arms.

Sebba 's book is engrossing, though often dense, difficult reading. But we should be grateful for her reminder that, for these amazing women, making music and art was Life itself.