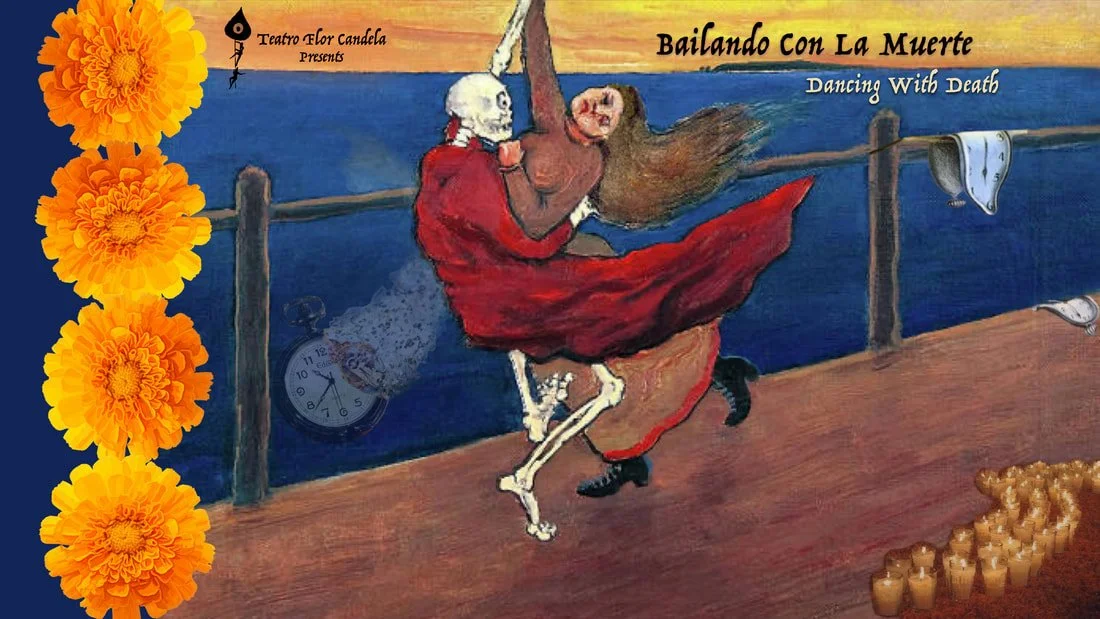

‘Bailando con la Muerte’ (Dancing with Death) @ Teatro Flor Candela

—Teresa Marrero

[NOTE: Review in English and Spanish.]

In Bailando con La Muerte, D-FW dance/theater/education collective Teatro Flor Candela transforms a familiar folkloric figure into a living, breathing dramaturgical force. In Mexican tradition, La Muerte has many names, among them La Catrina, a character created by José Guadalupe Posada and elaborated upon by Diego Rivera—a satirical, elegantly dressed lady skeleton who has become the face of Día de Muertos, the annual commemoration of those who have died. In this production, set in a funeral home (a great spot for the telling of personal stories about death), she is played with seductive wit by Diana Gomez, who also doubles as Tina, the funeral home assistant.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Performed at The Artstillery venue in Dallas’ Trinity arts district, he play begins in an intimate space facing a Day of the Dead altar dedicated to a woman and a man. A flutist dressed in black (Mike Johnson) introduces the atmosphere. Soon, married couple Claudia and Luis (Mariana Mariel and David Lemus) enter, bickering about how to arrange her mother’s and his father’s altar and ashes—two people who, we quickly learn, did not get along in life.

Their banter escalates into an unexpected “accident” in which both vessels of ashes tumble, shatter, and mix on the floor. Horrified, they attempt to gather the remains with a spoon—yes, an ordinary kitchen spoon—before giving up and deciding to scatter the merged ashes in the park where they played as children. In this opening, the tone is set: a blend of the seriousness of death with the ludicrous, chaotic humor of life. The entire performance unfolds primarily in Spanish, without translations, consistent with Teatro Flor Candela’s bilingual audience base. (However, some segments are in English.)

After this surprising prelude, the funeral director (Pedro Macias) and assistant Tina (Gomez) lead the audience to their seats near a centrally placed casket, an invitation for stories to gather around it. Next, Fidel (Ignacio Lujan) arrives to speak his final words to his deceased father; the emotions of their fraught relationship hover over the scene.

The next action introduces a woman in all black (Ana Lopez) who storms in wailing and sobbing. She is a professional Llorona, one of the women hired to cry at funerals. Her excessive lamentation offers both satire and commentary on ritualized grief. And then, an elegantly dressed older woman (Carmela Lamberti) begins recalling the virtues of her departed girlfriend—until the funeral director interrupts to inform her she is at the wrong funeral.

The audience erupts in laughter. The production mines these moments of misplacement to highlight the universality of mourning rituals.

Throughout the play, off to one side of the stage, sits a desk bearing a sign reading THE RADIO, its “ON AIR” light flashing each time the Announcer (Gloria Prieto) bursts in. Wearing a comically exaggerated male costume—including a jet-black Elvis pompadour and a painted mustache—Prieto delivers radio commercials, burial deals, and other absurdities that highlight the business aspect of death. As comic relief, her interruptions are sharp, well-timed, and frequently show-stealing. She is brilliant.

One of the most powerful scenes involves David (Lujan) recalling the death of his brother in Guatemala. Here, realism and myth intermingle. A mythological figure resembling Mictlantecuhtli, the Aztec god of death and the underworld, appears and dances in conchero style, forming an embodied bridge between the living and the dead. The scene suggests a Mesoamerican worldview in which death, memory, and the living coexist rather than contradict.

The final narrative scene brings all the characters together in a bar, where they unwind with drinks and reminiscences. This is where La Catrina (Gomez) makes her most dramatic entrance, reveling in coquettish seduction. Carmela Lamberti, now transformed into a male waiter, demonstrates impeccable comedic timing, rounding out the cast’s versatile interplay.

The piece concludes with an extended performance by Danza Azteca Quetzalcóatl, a conchero dance group from McKinney, Texas. Conchero dancers belong to a tradition that blends pre- Hispanic Indigenous ceremony, Catholic devotion, and post-conquest cultural continuity. Their ritual presence adds depth, history, and gravity to the performance’s closing moments.

Wearing large feathered headdresses—plumed with pheasant, eagle, and other feathers—the dancers move in arcs that sweep visually across the space. Their seed-pod ankle rattles, chachayotes or ayoyotes, lend a steady percussive rhythm to each step. Embroidered garments, beadwork, and mirrors on tunics blend Indigenous cosmology with colonial-era motifs. Their dance, both offering and invocation, expands the piece’s cultural and spiritual dimensions, linking ancient traditions to contemporary performance.

In Bailando con la Muerte, Teatro Flor Candela crafts an evening that is humorous, poignant, culturallylayered, and theatrically inventive—reminding us that death, in all its forms, is always dancing besideus. It is also a testimony to the perseverance and dedication of a small, Spanish-language company that has survived independently since 2007 in the Dallas area.

WHEN: November 15, 2025

WHERE: Artstillery, 723 Fort Worth Avenue, Dallas

WEB: teatroflorcandela.org

En español

En Bailando con la Muerte, Teatro Flor Candela transforma una figura folklórica familiar en una fuerza dramatúrgica viva y palpitante. En la tradición mexicana, La Muerte tiene muchos nombres; entre ellos, La Catrina, creada por José Guadalupe Posada y ampliada por Diego Rivera: una dama elegante y satírica, representada como esqueleto, que se ha convertido en el emblema del Día de Muertos. En esta producción es interpretada con seductora picardía por Diana Gomez, quien también da vida a Tina, la asistente de la funeraria.

Pero me estoy adelantando.

La obra inicia en un espacio íntimo frente a un altar de Día de Muertos dedicado a una mujer y a un hombre. Un flautista vestido de negro (Mike Johnson) introduce la atmósfera. Pronto aparecen Claudia y Luis (Mariana Mariel y David Lemus), un matrimonio que discute sobre cómo arreglar el altar y las cenizas de la madre de ella y del padre de él—dos personas que, como pronto descubrimos, no se llevaban bien en vida. Su discusión culmina en un inesperado “accidente” en el cual ambas urnas caen, se rompen y sus cenizas se mezclan en el suelo. Horrorizados, intentan recoger los restos con una cuchara—sí, una cuchara común de cocina—antes de darse por vencidos y decidir esparcir las cenizas mezcladas en el parque donde jugaban de niños. Con esta apertura queda establecido el tono: una combinación del peso de la muerte con el humor lúdico y caótico de la vida. Toda la representación transcurre principalmente en español, sin traducciones, lo cual concuerda con la base bilingüe del público de Teatro Flor Candela. Algunos segmentos se desarrollaron en inglés.

Tras este sorprendente preludio, el director de la funeraria (Pedro Macias) y su asistente Tina (Gomez) conducen al público a sus asientos. El espacio escénico principal es sencillo: un ataúd colocado al centro, convocando historias a su alrededor.

En la segunda escena, Fidel (Ignacio Lujan) llega para pronunciar sus últimas palabras frente al cuerpo de su padre fallecido—una relación tensa que permea el momento.

La tercera escena presenta a una mujer vestida completamente de negro que irrumpe llorando y lamentándose sin control. Es una Llorona profesional, interpretada por Ana Lopez, una de esas mujeres contratadas para llorar en funerales. Su lamento excesivo funciona como sátira y, a la vez, como comentario sobre el duelo ritualizado.

A continuación, una mujer mayor elegantemente vestida (Carmela Lamberti) comienza a recordar las virtudes de su amiga fallecida supuestamente en el ataúd—hasta que el director de la funeraria la interrumpe para informarle que está en el funeral equivocado. El público estalla en carcajadas. La producción aprovecha estos momentos de equívocos para subrayar la universalidad y, a veces, la absurda logística del duelo.

A lo largo de la obra, a un costado del escenario, se encuentra un escritorio con un letrero que dice THE RADIO, cuya luz de ON AIR se enciende cada vez que The Announcer (Gloria Prieto) irrumpe en escena. Con un vestuario cómicamente exagerado—incluido un copete negro estilo Elvis y un bigotico pintado de negro—Prieto ofrece anuncios radiales, comerciales, promociones funerarias y otras ocurrencias. Como alivio cómico, sus intervenciones son precisas, oportunas y frecuentemente se roban el aprecio del público. Prieto sencillamente brilla.

Una de las escenas más poderosas ocurre cuando David (Lujan) recuerda la muerte de su hermano en Guatemala. Aquí, realismo y mito se entrelazan. Una figura mitológica semejante a Mictlantecuhtli, dios mexica de la muerte y del inframundo, aparece y baila al estilo conchero, formando un puente corporal entre los vivos y los muertos. La escena sugiere una cosmovisión mesoamericana en la que la muerte, la memoria y lo sagrado conviven sin contradicción.

La escena final reúne a todos los personajes en un bar, donde se relajan entre tragos y recuerdos. Es aquí donde La Catrina (Gomez) hace su entrada espectacular, desplegando su seducción coqueta. Carmela Lamberti, ahora transformada en un mesero, demuestra un impecable sentido cómico que complementa la versatilidad del elenco.

La obra concluye con una extensa presentación de Danza Azteca Quetzalcóatl, un grupo de danza conchera de McKinney, Texas. Los bailarines concheros pertenecen a una tradición que mezcla ceremonia indígena prehispánica, devoción católica y continuidad cultural posconquista. Su presencia ritual aporta profundidad, historia y gravedad a los momentos finales.

Con grandes penachos de plumas—de faisán, águila y otras aves—los bailarines se mueven en arcos que recorren visualmente el espacio. Sus sonajas de semillas en los tobillos, chachayotes o ayoyotes, marcan un ritmo percutivo constante. Los atuendos bordados, las cuentas y los espejos en túnicas y mandiles combinan la cosmología indígena con motivos de la época colonial. Su danza, a la vez ofrenda e invocación, amplía las dimensiones culturales y espirituales de la obra, enlazando tradiciones antiguas con la performance contemporánea.

En Bailando con la Muerte, Teatro Flor Candela crea una velada humorística, conmovedora, culturalmente rica e inventiva en lo teatral—recordándonos que la muerte, en todas sus formas, siempre baila con nosotros. Es también un testimonio de la perseverancia y dedicación de una pequeña compañía de teatro en español que ha sobrevivido desde el 2007 en el área de Dallas.

Teresa Marrero, Ph.D. is Professor in the Department of World Languages, Literatures and Cultures at the University of North Texas. She specializes Performance Studies in Dance and Theater. https://class.unt.edu/people/m-teresa-marrero.html. Contact: Teresa.Marrero@unt.edu