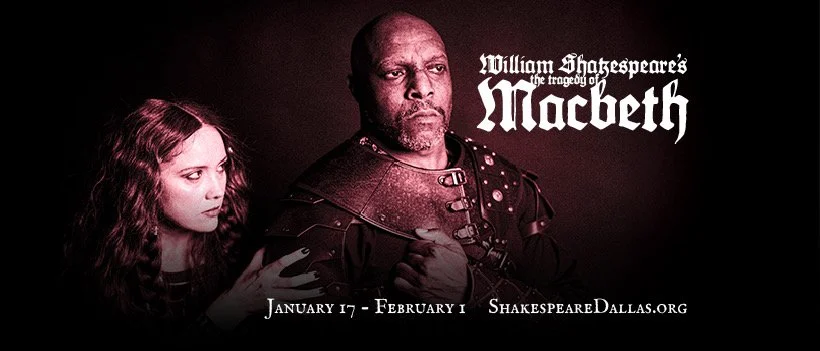

‘Macbeth’ @ Shakespeare Dallas (in Theatre 3)

Promotion photos by Kevin J. Hamm

—Ryan Maffei

Is that a dagger I see before me? I daresay I have a not-exactly-positive review to write. So brace yourselves, Macbeth company — at your best, you do great work, and I’d hate to enervate those good impulses.

One of the chief pleasures of going to any Shakespeare production — whether or not it turns out to be any good — is seeing what “hat,” if you will, has been placed upon the material. What time-warped new era, what arbitrary new geography, what completely unrelated aesthetic, what shoehorned-in theme? Where is our “vampire” Troilus and Cressida, and how long must we wait? Just short of 40 plays in the canon, but a thousand ways to gild a lily. I should note, in closing this catty paragraph, that it all has a 50% chance of working.

Shakespeare Dallas’ new Macbeth, presented at the Norma Young Arena at Theatre Three starting last Saturday (that’s the show I attended) surprised and rattled me with an even more novel twist than usual — namely, that I still have absolutely no idea what the “concept” was this time around. But here is my best attempt at roughly describing the opening. Folks, if YOU can glean answers from it (or got it instantly while watching the show), please write to us.

The theatre goes black. Epilepsy-triggering strobes and a blaze of neon green (plus a few other hues) throw light on our shrouded witches, circling a cauldron which will at one point be peed into. Audio mixed a bit too loud drops some familiar verses. My best-aimed stabs at capturing this in a word are “WWE” (the voice over contains a few of those glitchy, mock-edgy “skips,” and I really hope you know what I mean) or “rave” (I’m torn between whether to recommend you see this on MDMA or to fervently insist you don’t. Actually no: don’t.)

No idiots were involved here, but I am still trying to figure out what all that sound and fury signifies — as well as what it gives way to, a strange, pseudo-primitive choreo sequence in which the members of the company march and bend and a few other verbs around, if you’ll forgive my reductivity. (It is, perhaps, to indicate that they are puppets of cruel fate, but your guess is truly as good as mine.) It’s interesting in an imaginative way, at least, which is not quite how I’d characterize most of the rest of a terribly interesting production.

My chain of events may be a little shuffled, but rest assured — all of these things happen, and none return as epiphany-sparking motifs. The use of movement in this show — created by icon + local treasure Danielle Georgiou, an expert at foregrounding humanity in her ever-inventive work — is impactful and appealingly bizarre. Yet the performers don’t invest it with much clarifying commitment, though perhaps they were told not to. I would also (I say with the genuine human remorse people forget critics have) call David Saldivar’s fight choreo less than sharply-conceived — though to be fair, neither was that pun, so, call it a draw?

Much of this Macbeth, as I and perhaps you prefer, is couched in silence — the better to luxuriate in language and acting. But between scenes and at the end of key moments, the bursts of garish color and seizure-courting flashes and a bananas soundtrack kidnap your attention. Truly, what has SD’s Kellen Voss wrought? Make no mistake, I kind of love it, like I kind of love the aggressive, kitchen-sink way Lady Gaga sinks her teeth into kitsch. Ah, but when I didn’t like it, I felt the same way I do when I look at Born This Way’s cover – the one where Gaga is fused with a motorcycle. Many turn-of-[this]-century synths were deployed in the composition of these disorienting efforts, and even they provoke questions about taste.

As for the lighting, I would commend Aaron Johansen’s use of Day-Glo tones and shadow – this now gives me the chance to use the word “chiaroscuro,” thank you — but with the exception of the damn strobes. Johansen’s work may be the show’s most definitive element.

All of the above-cited aspects would appear to be clues about something that can often be a mystery on this side of the curtain — what, precisely, the director has brought to the table. Jenni Stewart is, as we know, a prolific and widely admired stager of ol’ Willy Shakes. But I wish I’d made more of an effort to find her or her AD Noah Heller after the show, and taken an opportunity to ask them about the work (presuming they wanted to give anything up). If you, future theatregoer, ask questions and get great answers, well, all’s well that etc. Still, one of the two things Stewart is unmistakably responsible for (placement of scenes around multiple levels of the Norma Young) were done rather more deftly and compellingly in last year’s Measure for Measure — and this time ranged from “inspired” to “I actually want a talkback.”

The other thing is the need of reconciling her performers. This has not occurred here, and the problem’s conspicuity was almost palpable at times — a shared experience. Reliable SD regulars onstage are stranded or stunted; worse, the two chief conspirators are too stylistically different to even begin to know how to combine their work. They do manage it in chance moments, as both find new and tender contours of roles we’re all pretty familiar with, and share a natural chemistry.

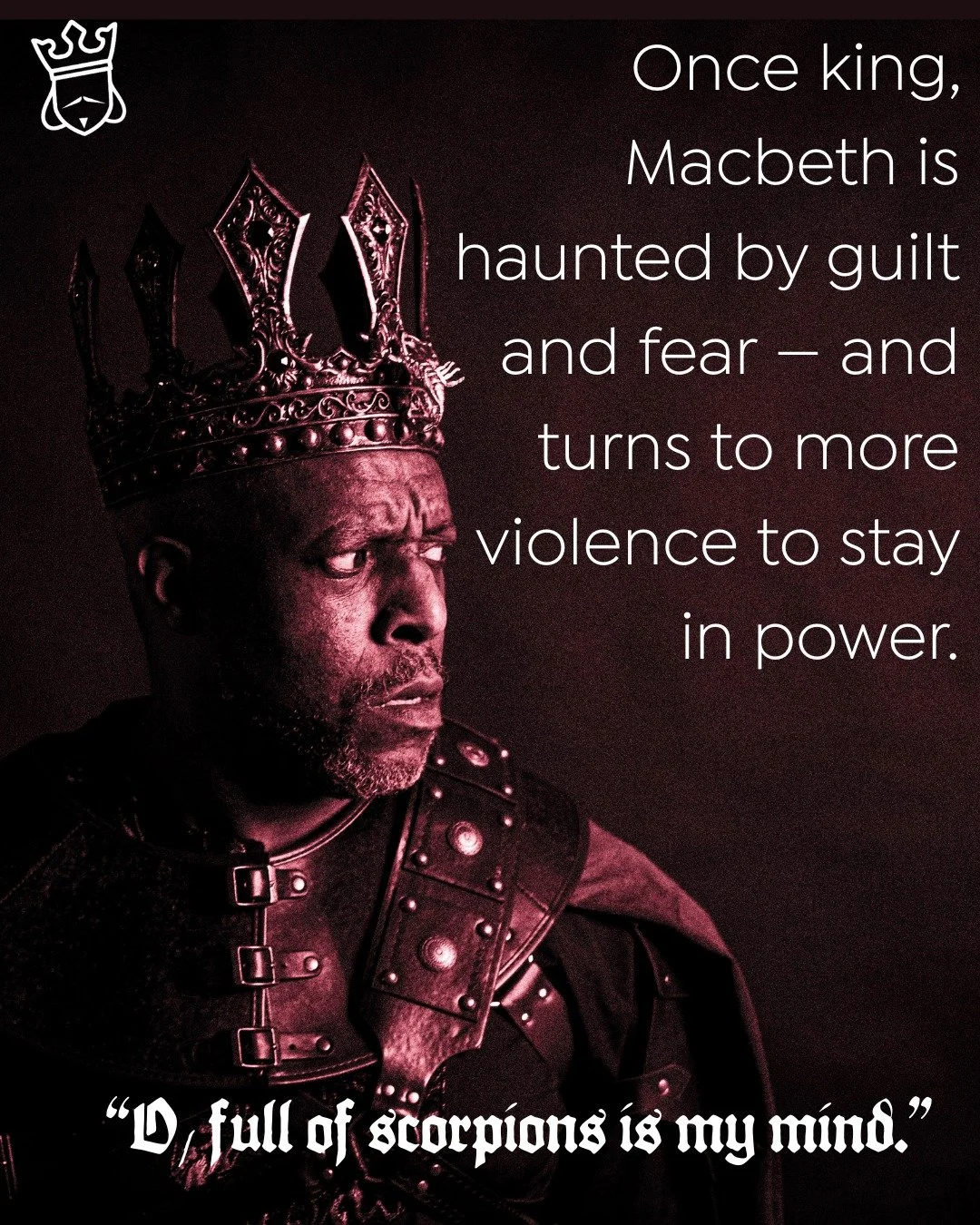

Brian Pitts is a stately, elegant Macbeth, who lets the verse flow like honey from his larynx. His characteriation of this royal usurper is more gentle than the norm, and at times a little stagey — at best like some of the more poetic representational styles, at worst like, well, shaky Shakespeare, empty and declarative. This Macbeth is a resonant study in the character’s softie soul, most poignant when counterposed against the strength Pitts is excellent at both reifying and undermining. But his is not a Macbeth who has really committed murder, nor lost his Lady (sorry, spoiler).

For a synthesis of coldhearted ambition and passionate vexation you’d be scared of encountering on the subway, look to Natalie Young as that Lady. Young is fantastic, at her best nearly as good as the role’s ever been played, lighting it up and luxuriating in its nuances. She elevates the production, and gives us something to hang onto during shellshocked lulls. The “spot” scene is particularly good, in a quiet way; not enough of this show is good in a quiet way. Yet Young doesn’t always seem of a piece with her surroundings, and at times, you feel for her over it.

Others make disparate impressions. Adrian Godinez absolutely feels it as MacDuff, but he tends to like a lighter brush and limited palette, which flourishes in comedy but isn’t always as alluring on an aggro-drama canvas. Yet at his best, he’ll make you cry. Brandon Whitlock always finds great twists on familiar lines, and does so here, if fewer and further in between than usual (he’s often offstage or cloaked). Jon Garrard finds a welcome levity as Malcolm, but though he’s such a smart actor, he doesn’t define this character much. Omar Padilla is never not witty and fun to watch, and joins his aforementioned bros in feeling underutilized.

The true highlights come from unexpected corners. Dennis Raveneau had the audience in stitches with his garrulous extended Porter routine; he’s very good as the Doctor as well. T. A. Taylor is a soulfully weary King Duncan, fully believable. Jasonica Moore’s restrained yet almost unbearably emotional work as Lady MacDuff was fantastic, my personal favorite in the entire show. And while Efren Paredes doesn’t vary all that much from his charmingly earthbound Biondello in Taming last year, this play requires a pathos he inhabits well.

Nicole Berastequi is a hoot as Hecate and her Ross is strong, though I could swear I saw bite marks on Cody Stockstill’s solid, sturdy set after she’d left. (Berastequi is joined by Moore, Young and Whitlock as her hard-to-pin-down witches). Scenographer Korey Kent has done commendable, ultimately minimalistic work, and his costumes are quite good (though the reference is neither here nor there, Lady Macbeth looks like Merida from Disney’s Brave, and Brave is great). The costumes pair well with Cindy Ernst Godinez’s top-notch props—yet part of why this Scottish Play seems short of a unifying aesthetic is the absence of a cohesive one visually. On the plus side, however, the show looks like it was a beast to stage manage, and Grace Hellyer has, er, killed it.

Brilliant local satanist (she told me I could say that) Isa Flores, one of the nicest people ever as well as someone who’d pluck your eye out with her nail, earns the double-take title of “gore designer.” At this rate Flores will be the nation’s best by the time free elections have been suspended (i.e. less than half a decade). She is responsible for a moment that is even more disquieting than the schoolgirl beheading in Circle’s Theatre’s recent Mac Beth, something I truly did not believe was achievable. Hers is a brutally dark set piece; Flores does her job with the usual artful zest and incomparable attention to detail. (I think, anyway, as I had to turn away instantly.)

One cannot blame Flores for the questionable sensitivity of this moment, or another one that bears her stamp. But one can blame someone, for that and the way this Macbeth was not, at times, a good time. Abjuring politics, to say nothing of significance, is still legal in this free-ish country, and escapism still has serious value. But part of what’s so compelling about stories like Macbeth is that they ask questions about politics, power and violence. If you’re gonna put it on in these troubled times, you’d do well to double-check your whys. All that courage will get lonely screwed into a sticking place that holds no clear convictions.

WHEN: January 17–February 1, 2026

WHERE: Theatre Three, 2688 Laclede St., Dallas

WEB: shakespearedallas.org