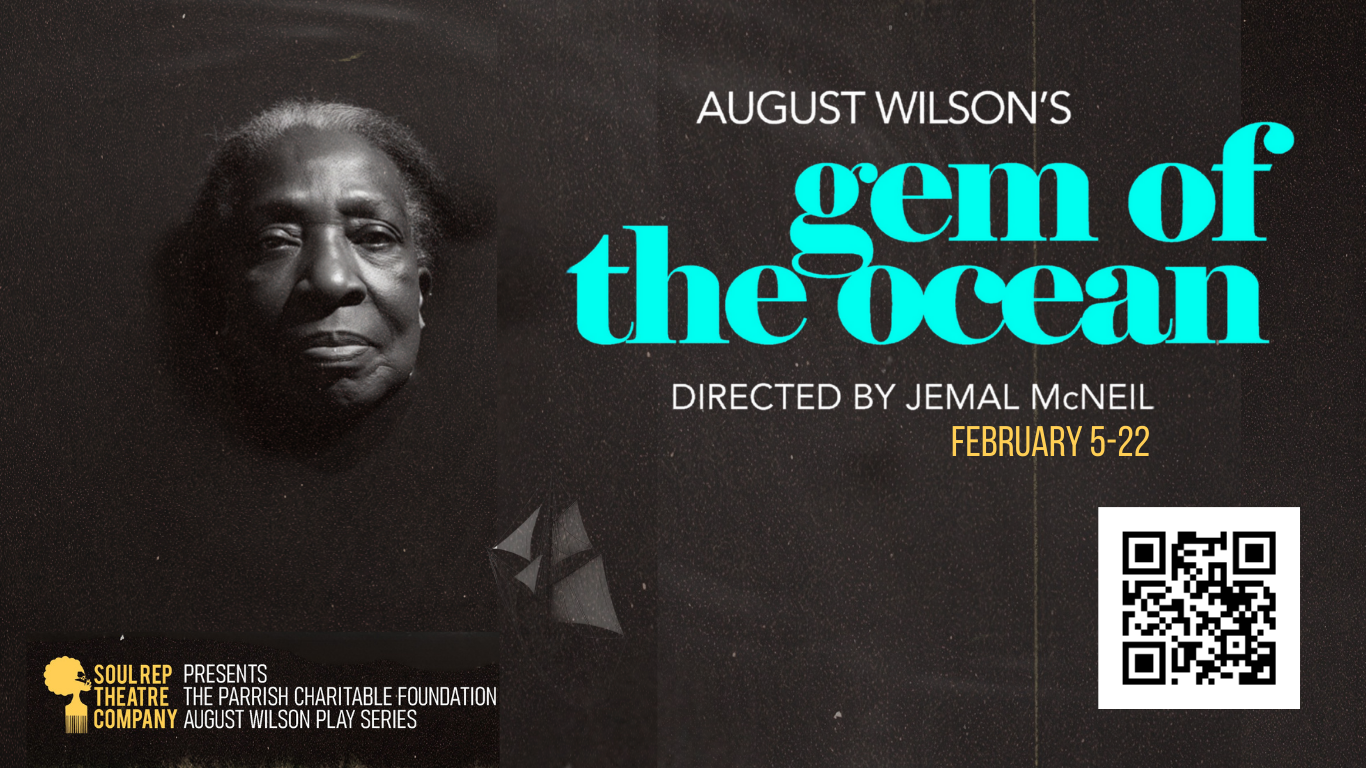

August Wilson’s ‘Gem of the Ocean’ @ Soul Rep Theatre

Photos courtesy of Ashley Oliver, Soul Rep

—Rickey Wax

“Ain’t nothing wrong with you that ain’t been wrong with somebody else.”

Aunt Ester says it plainly. It lands early in August Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean, and in Soul Rep Theatre’s production it becomes the spine of the entire night. It reminds us that suffering is not unique, but responsibility is—a trial and obligation each of us must carry in our own way. And it reminds us that healing, sometimes inconveniently, is a group project. With this production, Soul Rep kicks off Black History Month by asking what parts of that history we are still carrying.

Wilson sets the play in 1904, inside Aunt Ester’s home at 1839 Wylie Avenue in Pittsburgh, a place people come to when the world has closed in on them. Director Jemal McNeil keeps the focus there. Gabrielle Malbrough’s set gives us a worn but lived-in home. Wood shutters, wooden planks, chairs, an old-timey stove. It feels grounded. The kind of place where stories live in the walls whether you want them to or not. One of the most effective touches comes from Troy Carrico’s lighting. Whenever Aunt Ester enters, the lights flicker. It is subtle, but noticeable. It tells you this house responds to her. (Or perhaps more truthfully, it answers to her.)

Keira Powers’ costumes root the production firmly in 1904: a man’s worn coat, careful attention to period shoes, suspenders, and trousers, Aunt Ester’s richly colored cape (she calls it her shawl) that recalls a kind of Joseph-like mantle of many colors. Her gele-style head wrap sits on her head like a crown, quietly signaling both her spiritual authority and the generations she carries with her.

The play opens with Citizen Barlow knocking. Brian Gibson plays him as a man already carrying shame. He tells Aunt Ester, “I ain’t come for no charity. I come to see you.” He doesn’t want pity. Maybe forgiveness? Perhaps permission to forgive himself.

Renee Miche’al Jones’ Aunt Ester keeps it steady. She listens first. Then she speaks. When she tells him, “You got to carry it. You got to carry it with you,” it’s instructional. Not cruel. Not gentle either. Just true. Jones lets silence do most of the work. She understands authority rarely needs to raise its voice.

Inside the home is Eli, played by J.R. Bradford. He watches everything. Eli is protective of the space and of Aunt Ester. Black Mary, who is Aunt Ester’s protégé and played by Anyika McMillan-Herod, lives there too. At first, she keeps her distance from the newly arrived Citizen. She says, “I ain’t studying him” (Girl who are you foolin?), but she still watches him. Over time, her guard softens. She begins to let her hair down, both figuratively and literally, stepping more fully into her own womanhood.

Between scenes, the characters sing acapella Negro spirituals—“Wade in the Water” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”—that add a stirring touch to the show. These songs are intentional. They carried coded meaning for enslaved people. They spoke about escape, death, survival, and hope. They were maps. They were prayers. They were warnings. Here, they help transition us from one emotional space to another.

Solly Two Kings enters singing “I belong to the band.” Douglas Carter plays him as someone who has already made his peace with who he is. Solly talks about freedom often. At one point he says, “If you ain’t got your freedom, you ain’t got nothing.” Carter gives Solly a grounded presence, adding a slight stutter and a limping walk with his notched stick. He understands freedom is something he has had to claim and continue claiming.

Nash Farmer’s Selig brings in outside news. He’s a white man (and like Aunt Ester appears in some form in several of Wilson’s plays) who moves through communities, collecting and selling items, but also stories. Selig’s commentary reminds us that the world outside this house is still hostile. That sanctuary is temporary. That reality always finds you.

That hostility shows up fully in Caesar, Black Mary’s brother, played by Angelo Reid. Caesar believes in law and order. He says, “This is Pittsburgh. This ain’t Alabama. You got to follow the law.” Reid lets Caesar stand firm in his authority. He believes in the law because it gave him somewhere to stand. But when Aunt Ester tells him, “That piece of paper don’t mean nothin,” it exposes the truth he avoids. The paper didn’t free him. It just gave him something to defend. In his mind, he is right. (Oppression sometimes looks respectable.)

Each character is trying to survive something. Citizen carries guilt after a man died because of him. Black Mary carries anger and disappointment. Solly carries memory, and still grapples with what freedom truly is to him. Caesar carries power. Aunt Ester carries history. And history, Wilson reminds us, is never past, never done.

The turning point of the play comes when Aunt Ester tells Citizen that to “get right with yourself” he must go to the City of Bones beneath the ocean. She tells him, “You got to go there and see it.” The lighting shifts. Blue and magenta tones fill the stage. The world changes and becomes at one time more internal, and more steeped in their history. This moment is about confrontation. Gibson gives a captivating performance here, and it is heightened once Black Mary brings out the African drum and begins pounding on it. The drum becomes ritual. In many African traditions, it is used to call ancestors and guide spiritual crossing. Each strike pulls Citizen closer to himself.

Wilson wrote Gem of the Ocean as part of his American Century Cycle, ten plays covering each decade of the 20th century. Even though he wrote this play later in his life, it takes place earliest in the timeline. Aunt Ester appears throughout Wilson’s cycle as an unseen but often invoked spiritual presence. (Gem marks Aunt Ester’s only stage appearance in the cycle; in other plays she is spoken of or visited for advice, but offstage.) She represents memory that refuses to disappear. Because someone has to remember when others would rather forget.

Soul Rep’s production builds carefully toward its final moments. Right before everything changes, Aunt Ester tells Citizen, “You got to wash yourself.” As we all must do at some point in time. With truth. (And truth, unfortunately, does not care how long you’ve avoided it.)

There were a few small line stumbles, but nothing that took away from the story. The cast remained present; Wilson’s play keeps asking them (and all of us) the question: What do you do about what you carry, and will there come a time when you can finally let it go?

WHEN: February 5-22

WHERE: South Dallas Cultural Center, 3400 S Fitzhugh Ave, Dallas

WEB: www.soulrep.org