‘Medea/Liturgia’ @ Cara Mia Theatre Company

Photos courtesy of Cara Mia Theatre Co.

—Teresa Marrero

Spanish version follows below….

Medea/Liturgia, written and directed by Diego Fernando Montoya, and winner of Colombia’s 2025 National Prize for Dramaturgy, opened February 12 in the Latino Cultural Center Black Box Theatre, in full creative collaboration with Cara Mía Theatre Company.

However, the piece begins in the foyer, immersing the audience within the world of myth and liturgy. The stark program quote ¨No homeland at my back, no refuge ahead¨ sets the political and ritual tone.

Background of the Myth

In Greek mythology, Medea is a princess of Colchis and a gifted sorceress who falls in love with Jason when he arrives in search of the Golden Fleece. To secure his success, she betrays her father, King Aeëtes, uses her knowledge of magic to help Jason complete a series of deadly trials, and flees her homeland with him. Years later, after they have settled in Corinth and had children, Jason abandons Medea to marry the king’s young daughter, Glauce, in pursuit of political power, leaving Medea doubly marginalized as wife and foreigner. In revenge, she kills Jason’s new bride and her own children before escaping, sealing the myth as one of antiquity’s most devastating meditations on betrayal, exile, and sanctioned violence, themes exalted in Medea/Liturgia.

In the beginning…

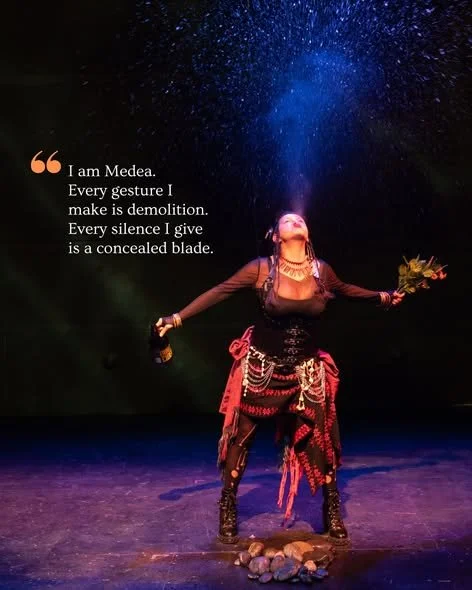

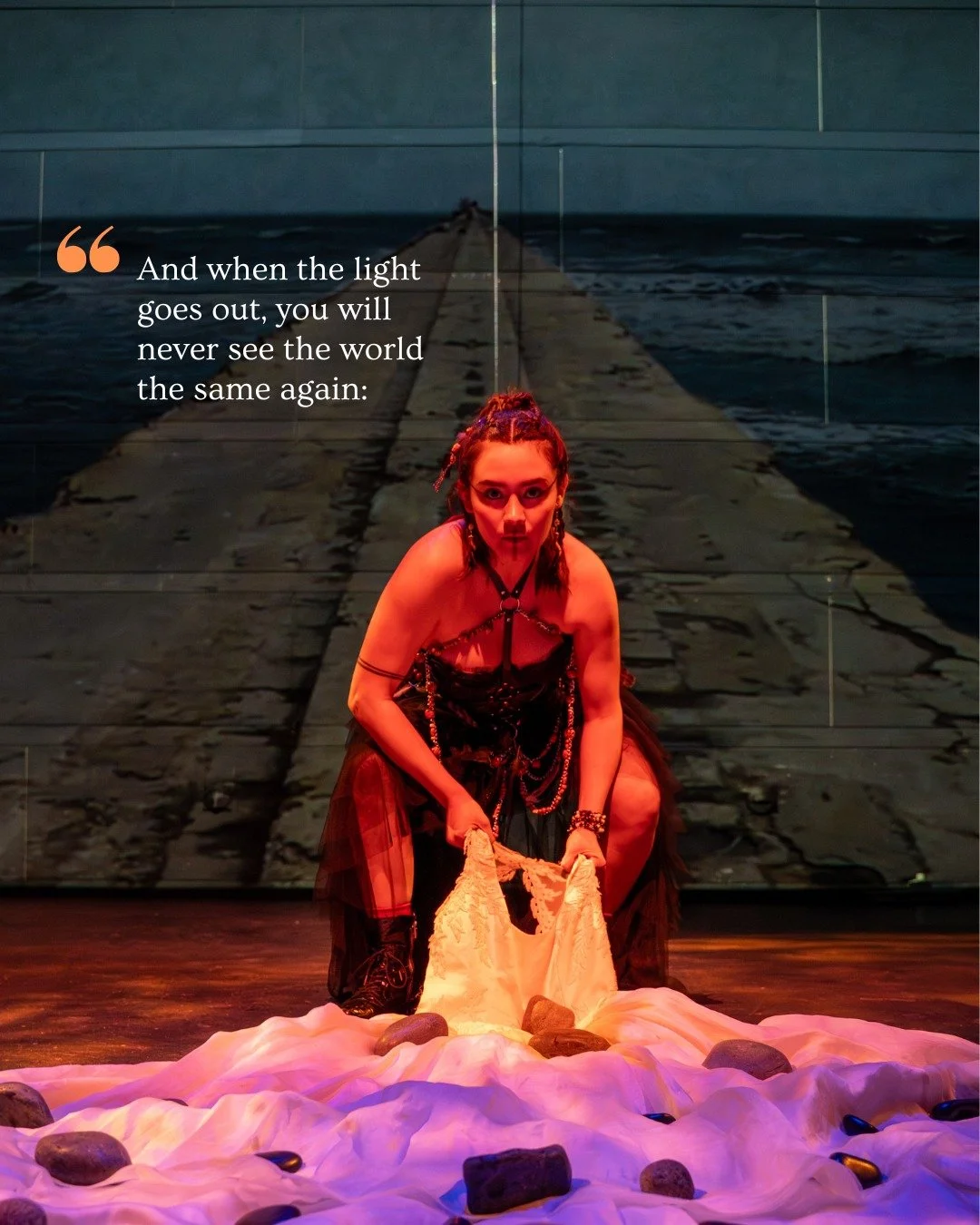

A woman draped in black lace enters the space and circulates among the standing audience members, ready to enter the theatre. As she does, another woman shrouded in white cloth enters and stands on a small platform atop a pile a smooth stones—and then three other women, dressed in post-apocalyptic black with some red. They move around the central figure, eventually unwrapping her body and leaving her vulnerable and almost naked. Meanwhile the three red/black women pass out stones to audience members, who are invited to stone the women in the center. I overheard a real fear that someone might actually throw a stone. And then spontaneous whispers from the crowd emerged: “Don’t do it.”

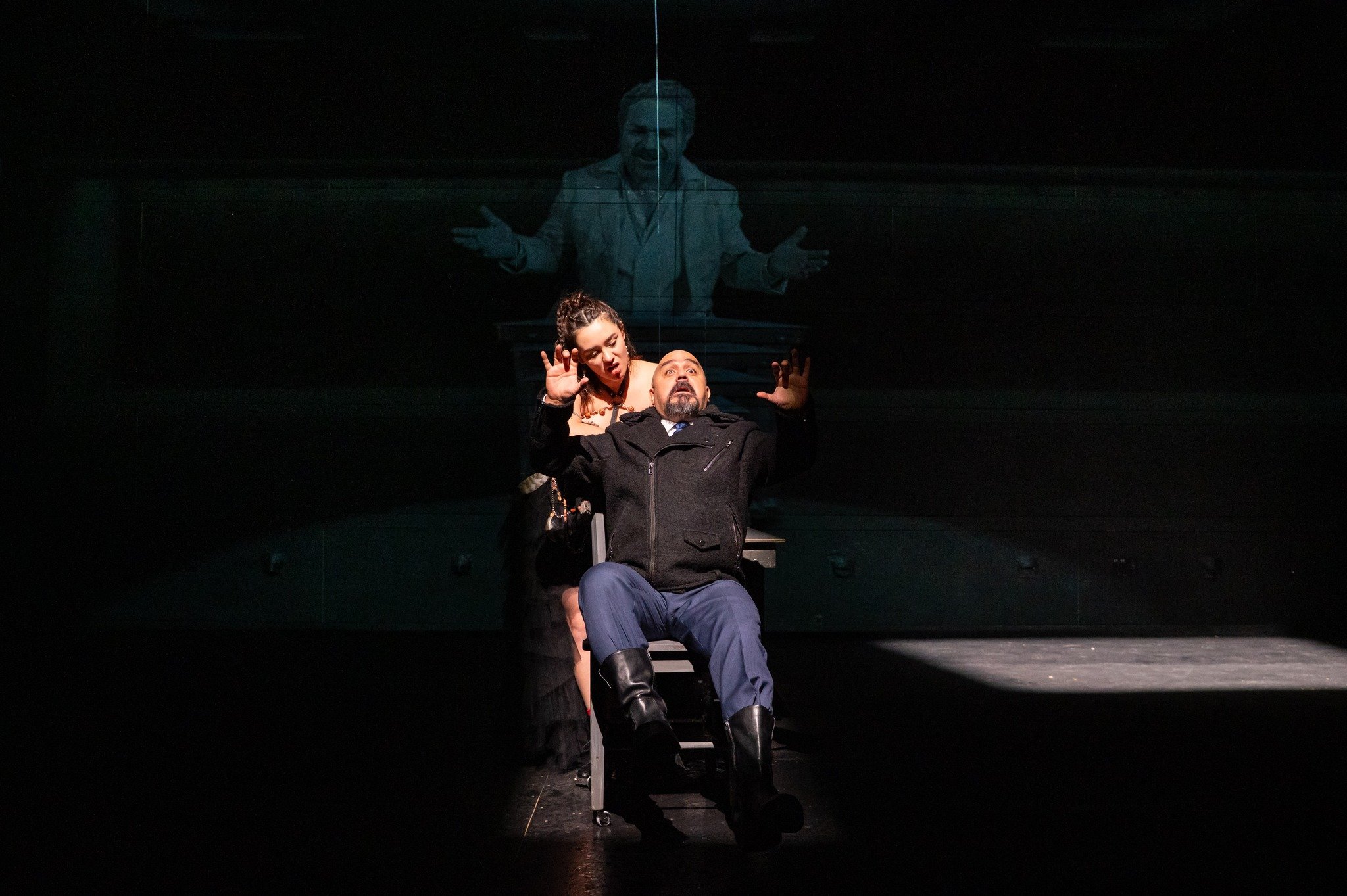

The audience was then led inside the theatre space, which was open giving a sense of expansion. Shoes of all sizes were laid out to demarcate the performance space. A huge projection played against the back wall. It was the sea, with a jetty extending from the middle, war ships visible off to one side and a wall off to the other. A huge table extended before us, and there were visible props off to the sides.

This is clearly the most descriptive I can get because what followed for the next hour of the performance felt like a dense stream of consciousness composed of captivating poetry and actions by the now-evident four Medeas (Freda Espinosa Müller, Sorany Guitiérrez, Lucila Rojas and Stephanie Oustalet, who also played Glauce).

Because I am bilingual in Spanish and English the flow between languages at first was imperceptible. The Medeas and Jason-Creon (David Lozano) delivered segments entirely in English and then in Spanish without the usual trope of repetition or overhead translations (although in one segment there were). Later, I wondered what the experience of a monolingual audience member might have been.

The Liturgical Frame as Structure, Not Ornament

In Medea/Liturgia, the liturgical dimension is not aesthetic garnish; it is the architecture of perception. Liturgy organizes time. It provides the tempo of the words, of the movements. Medea/Liturgia breaks with conventions. It is multiple, catastrophic and grounded in today´s problematic issues concerning immigration, the abuse of power by governmental forces, the bombing and destruction in the Middle East, the fetishism of child abuse as suggested by the Epstein files debacle. In Medea/Liturgia, the character of Medea is multiplied and distributed across four bodies. The liturgical mode makes this multiplication legible. Ritual disperses authorship; it creates communal utterance. The four Medeas do not fracture identity; they officiate it with a sense of urgency and anger. They empower themselves to speak raw truths, to break down the old systems of thinly veiled deception by structures of power.

The audience does not simply witness her suffering; we are positioned as congregants. The theatrical event borrows from the logic of ritual: the invocation to remember, the utterance of truths, the sacrifice endured by the less powerful, and the lamentation of mothers who see their children sacrificed to the whims of war. The repetition of gestures and poetic articulation produces what feels less like plot progression and more like cyclical remembrance. War, then, is not a singular act committed by Jason or Creon. It is exposed as a doctrine rehearsed by power.

A Multiplicity of Voices as Political Theology

The original Greek tragedy relies on the chorus as civic witness. But here the chorus is Medea. The communal female body becomes both officiant and offering. The liturgical multiplicity of voices destabilizes the solitary tragic heroine and replaces her with collective testimony.

This matters politically. If Medea becomes metaphor for the weaponization of foreignness, then liturgy exposes how ideology spreads: through repetition of certain narratives at the expense of others. Jason’s logic, the conquest, betrayal and nation-building through abandonment, reads like a creed recited often enough to feel inevitable. The Medeas expose and break this pattern. The production does not merely depict violence; it stages the ritual mechanisms that justify it.

Medea/Liturgia does not seek absolution. It stages remembrance and outrage. By invoking liturgy, the production implicates the structures (religious, national, patriarchal) that sanctify violence against the foreign body. The tragedy is not that Medea kills; it is that the world has already consecrated her expendability as woman, as other, as foreign.

In this staging, every woman becomes altar and priest, exile and prophet. And Jason’s war, rehearsed through centuries, reveals itself not as aberration but as political ambition here disrupted by poetry and visual rearticulation.

This formidable play is so dense with meaning, poetry and imagery that it begs to be seen again and again. And its success lands squarely on the evident energy and total commitment of the playwright/director, the performers, and the production team.

WHEN: February 12-22, 2026

WHERE: Latino Cultural Center, 2300 Live Oak Street, Dallas

WEB: caramiatheatre.org

[This bilingual production contains brief non-sexual nudity and adult themes, and is recommended for ages 18+ or with parental guidance. Languages include English, Spanish, and Arabic.]

En español:

Medea/Liturgia, escrita y dirigida por el director invitado Diego Fernando Montoya, Premio Nacional de Dramaturgia de Colombia 2025, se estrenó el 12 de febrero y se presenta hasta el día 22 en el Black Box Theatre del Latino Cultural Center en completa colaboración con Cara Mía Theatre Company. Sin embargo, la pieza comienza en el vestíbulo, sumergiendo al público en el mundo del mito y la liturgia. El programa cita: ¨Sin patria a mi espalda, sin refugio por delante,¨ estableciendo desde el inicio el tono político y ritual.

Antecedentes del mito

En la mitología griega, Medea es una princesa de la Cólquide y una hechicera dotada que se enamora de Jasón cuando este llega en busca del Vellocino de Oro. Para asegurar su éxito, ella traiciona a su padre, el rey Eetes, utiliza sus conocimientos de magia para ayudar a Jasón a superar una serie de pruebas mortales y huye con él de su patria. Años más tarde, tras establecerse en Corinto y tener hijos, Jasón la abandona para casarse con la joven hija del rey, Glauce, en busca de poder político, dejando a Medea doblemente marginada como esposa y extranjera. En venganza, Medea mata a la nueva esposa de Jasón y a sus propios hijos antes de escapar, sellando el mito como una de las meditaciones más devastadoras de la Antigüedad sobre la traición, el exilio y la violencia sancionada, temas exaltados en Medea-Liturgia.

En el comienzo…

Una mujer encubierta por encaje negro entra al espacio y circula entre el público, parados listos para ingresar al teatro. La entrada se retrasa cuando otra mujer, envuelta en tela blanca, aparece y se coloca sobre una pequeña plataforma situada encima de un montón de piedras lisas. Luego entran tres mujeres más, con un vestuario de negro con toques en rojo que sugiere un pos-apocalípsis. Se mueven alrededor de la figura central, hasta finalmente desenvuelven su cuerpo, dejándola vulnerable y semidesnuda. Mientras tanto, las tres mujeres reparten piedras entre los espectadores. En un momento dado, surge la sugerencia por parte de las mujeres a apedrear a la del centro. Sentí un temor real de que alguien pudiera lanzar una piedra. Y entonces surgieron murmullos espontáneos entre el público: «No lo hagan».

Luego el público fue conducido al interior de la sala teatral, un espacio abierto que producía la sensación de expansión. Zapatos de todos los tamaños estaban dispuestos para demarcar el área escenográfica. Una enorme proyección ocupaba la pared del fondo: el mar, con un muelle que se extendía desde el centro, barcos de guerra visibles a un lado y un muro al otro. Una gran mesa se extendía frente a nosotros, y había utilería visible a los lados.

Este es, claramente, el punto más descriptivo al que puedo llegar, porque lo que siguió durante la próxima hora se sintió como un denso fluir de conciencia compuesta de poesía y acciones hipnotizantes por las ya evidentes cuatro Medeas (Freda Espinosa Müller, Sorany Guitiérrez, Lucila Rojas y Stephanie Oustalet, quien también interpretó a Glauce).

Como soy bilingüe en español e inglés, el flujo entre los idiomas me fue, al principio, casi imperceptible. Las Medeas y Jasón-Creonte (David Lozano) interpretaron segmentos completamente en inglés y luego en español, sin recurrir al tropo habitual de la repetición o la traducción proyectada (aunque en un segmento sí la hubo). Luego me pregunté cómo habrá sido la experiencia para un espectador monolingüe en cualquiera de los dos idiomas.

El marco litúrgico como estructura, no como ornamento

En Medea/Liturgia, la dimensión litúrgica no es un adorno estético; es la arquitectura de la percepción. La liturgia organiza el tiempo. Proporciona el tempo de las palabras y de los movimientos. Medea/Liturgia rompe con las convenciones. Aquí Medea es múltiple, catastrófica y anclada en las problemáticas actuales en torno a la inmigración, el abuso de poder por fuerzas gubernamentales, los bombardeos y la destrucción en Medio Oriente, y el fetichismo del abuso infantil sugerido por el escándalo de los archivos Epstein. En esta versión, Medea se multiplica y se distribuye en cuatro cuerpos. El modo litúrgico hace legible esa multiplicación. El ritual dispersa la autoría; crea una enunciación comunitaria. Las cuatro Medeas no fracturan la identidad; la ofician con urgencia y rabia. Se empoderan ellas mismas para decir verdades crudas, para desmantelar los viejos sistemas velados de engaño sostenidos por las estructuras del poder.

El público no simplemente presencia su sufrimiento; es situado como congregación. El acontecimiento teatral asume la lógica del ritual: la invocación a la memoria, la enunciación de verdades, el sacrificio soportado por los menos poderosos y el lamento de las madres que ven a sus hijos sacrificados a los caprichos de la guerra. La repetición de gestos y de articulaciones poéticas produce una sensación menos de progresión narrativa que de memoria cíclica. La guerra, entonces, no es un acto singular cometido por Jasón o Creonte. Es expuesta como una doctrina ensayada por el poder.

Multiplicidad de voces como teología política

La tragedia griega original se apoya en el coro como testigo cívico. Pero aquí el coro es Medea. El cuerpo femenino comunitario se convierte tanto en oficiante como en ofrenda. La multiplicidad litúrgica de voces desestabiliza a la heroína trágica solitaria y la reemplaza por un testimonio colectivo.

Esto importa políticamente. Si Medea se convierte en metáfora de la instrumentalización de la extranjería, la liturgia revela cómo se difunde la ideología: mediante la repetición de ciertas narrativas a expensas de otras. La lógica de Jasón—conquista, traición y construcción de nación a través del abandono—suena como un credo recitado con suficiente frecuencia hasta parecer inevitable. Las Medeas exponen y quiebran ese patrón.

La producción no se limita a representar la violencia; escenifica los mecanismos rituales que la justifican. Medea/Liturgia no busca absolución. Escenifica memoria e indignación. Al invocar la liturgia, la puesta en escena implica a las estructuras (religiosas, nacionales, patriarcales) que santifican la violencia contra todo cuerpo extranjero. La tragedia no radica en que Medea mate; radica en que el mundo ya ha consagrado su carácter desechable como mujer, como otra, como extranjera.

En esta puesta en escena, cada mujer se convierte en altar y sacerdotisa, exiliada y profeta. Y la guerra de Jasón, ensayada a lo largo de los siglos, se revela no como aberración sino como ambición política, aquí interrumpida por la poesía y la rearticulación visual.

Esta formidable obra es tan densa en significado, poesía e imaginería que invita a verla una y otra vez. Y su éxito recae de manera contundente en la energía evidente y el compromiso absoluto del dramaturgo/director, los actores y el equipo de producción.

[Esta producción bilingüe contiene breve desnudez no sexual y temas para adultos; recomendada para mayores de 18 años o con supervisión parental. Los idiomas incluyen inglés, español y árabe.]

Teresa Marrero es Profesora de Teatro y Cultura Latinoamericana y Latinx en el Departamento de World Languages, Literatures and Cultures de la University of North Texas. Teresa.Marrero@unt.edu