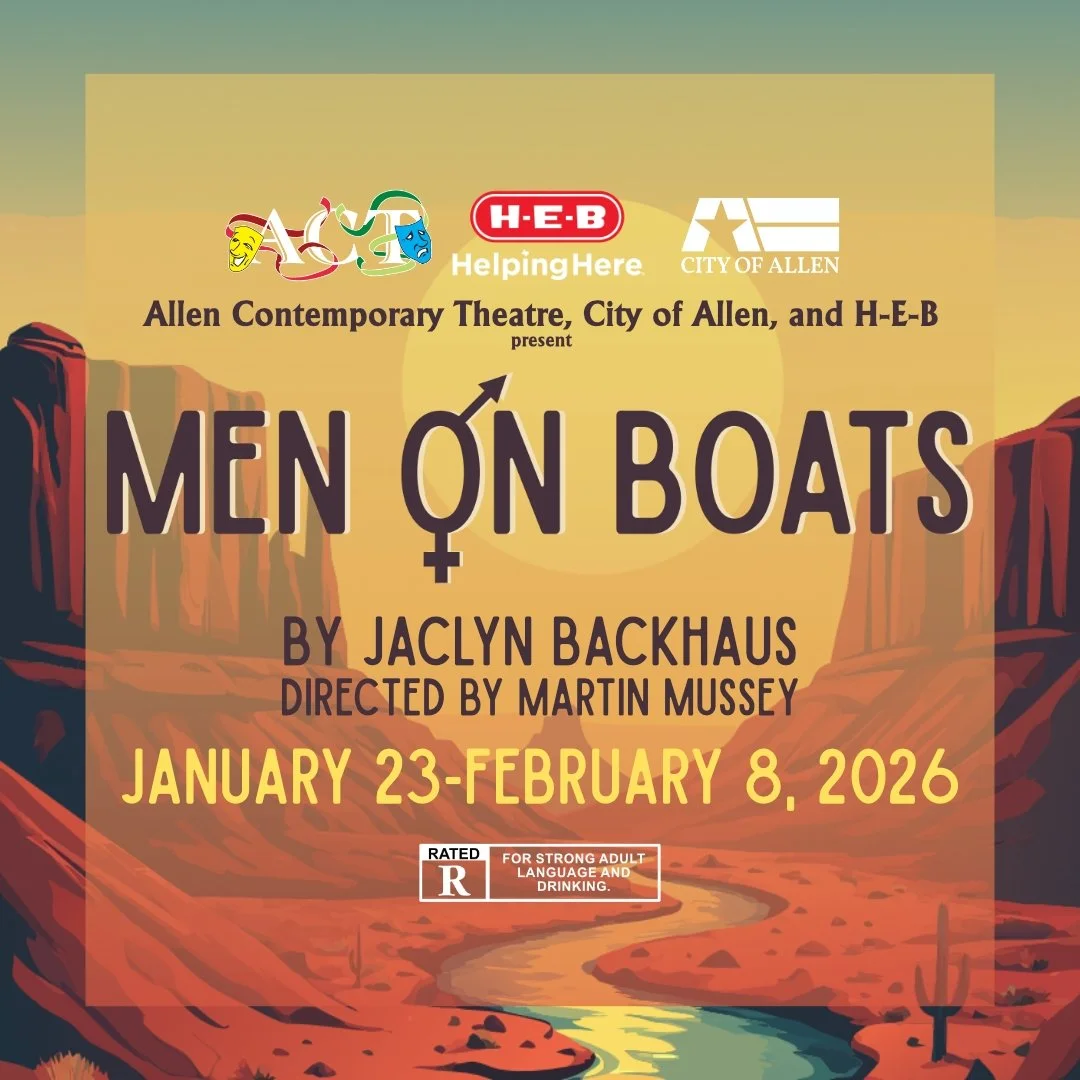

‘Men on Boats’ @ Allen Contemporary Theatre

Production photos by Jess Harley Photography

—Rickey Wax

Allen Contemporary Theatre kicks off its season with Men on Boats, a reminder that nothing says “new year” quite like hubris, history, and a river that really doesn’t care. I enjoy coming to Allen Contemporary because I know three things will always be waiting for me: soft peppermints in a bowl, fresh popcorn somewhere in the vicinity, and good old-fashioned thespians doing what they do best—trusting the audience enough to let imagination do half the work. No gimmicks. Just artists, grit, a room, and a shared agreement to believe.

Which makes Men on Boats the perfect fit for this space.

Four wooden chairs sit in formation. These are the boats—the Emma Dean (named after the captains wife), No Name, Kitty Clyde, and Maid of the Canyon—and they are ready to be pushed downstream by ten men who believe that they are about to be remembered forever. (Sorry fellas, history has other plans.)

Jaclyn Backhaus’ Men on Boats, directed by Martin Mussey, opens by announcing itself as “true-ish,” which is theatrical shorthand for we’re about to interrogate the lie of truth itself. This is the 1869 Powell expedition down the Colorado River, yes—but refracted through a contemporary lens that dismantles the mythology of conquest almost as fast as it builds it. The river, we’re told early on, “doesn’t care about you,” and the production takes that idea seriously.

Backhaus’ insistence on an all women, trans, and nonbinary cast is a deliberate act of interrogation, meant to de-center white male authority without erasing it. Men on Boats is, after all, a play about white men, Manifest Destiny, and the mythology of American conquest—but casting performers historically excluded from these narratives forces the audience to see the power structure instead of unconsciously accepting it. Masculinity becomes something performed rather than assumed, leadership reads as learned behavior, and history begins to feel less inevitable and more like a series of choices—some brave, some foolish, and many deeply human. The effect creates a critical distance, the jokes land sharper because we aren’t trapped inside reverence or realism. NOW, we can truly examine these men.

We meet Major Powell first, steady and self-assured, as Kathleen Vaughn anchors the expedition. Powell’s a man who believes leadership is his birthright but understands it still requires effort. Vaughn’s restraint becomes increasingly important as the play asks whether competence and entitlement are too often confused.

The crew assembles rapidly, and Mussey keeps the pacing brisk. William Dunn (Dahlia Parks) barrels into scenes with chaotic energy (which is everything and more). Parks’ unpredictability is a feature and you can feel the audience lean forward, waiting to see whether Dunn will shout, joke, or unravel next (sometimes all three). John Colton Sumner, played by Maxine Frauenheim, brings tightly wound anxiety to the early stages of the journey. This is a man obsessed with legacy.

Old Shady, embodied by Molly Bower, drifts in and out of the narrative like a reminder that someone is always watching—and every now and then also serves as the personal jukebox, human edition. Part narrator, part conscience, part warning label, Bower understands exactly when to lean into humor and when to let the weight of inevitability settle. Bradley, played by Harper Caroline Lee, is as cute as a button. In particular, the scene where he takes his pants off to save someone (I won’t ruin it) had me almost in stitches.

Mussey’s direction embraces Backhaus’ contemporary language. When the men talk about discovery—about being first—it lands as revealing. They want to be seen, and are even willing to risk their lives to ensure it happens. In true American Manifest Destiny fashion, the script keeps reminding us that people already lived here, knew this river, and survived it—facts history tends to footnote. That tension becomes the play’s undercurrent. (I’m so clever.)

The choreography, also by Lee, transforms minimal elements into a living, relentless environment. Wooden chairs tilt, collide, and collapse. A simple sheet becomes rushing water and a merciless waterfall. Bodies lean at impossible angles, defying gravity (I just couldn’t help myself) and fear. This is actor-driven stagecraft, both imaginative and demanding. Lighting by Melinda Cotton washes the stage in dusty ambers and melancholy blues, while Greg Cotton’s sound design keeps the river ever-present, sometimes quiet, sometimes roaring. The danger is always apparent in each scene.

Costumes by Shanna Threlkeld ground the ensemble in a loose historical palette—plaids, browns, maroons—with just enough specificity to suggest period without trapping the actors inside it. (Yes, Powell’s blue shirt does its symbolic duty.)

As Act One progresses, egos are tested and you can cut the testosterone with a knife. Rations dwindle (who wouldn’t be sad that we ran out of bacon?), alliances are tested, and each of these men ask themselves internally if this is even worth it anymore. The ensemble collectively ensures that every member of the expedition is distinct. No one fades into the background; each performer understands their character’s relationship to power, fear, and survival. Rather than opt for the overplayed “heroic” figure, the playwright taps more into their humanity as each one’s superpower. They are anxious, arrogant, tender, ridiculous humans clinging to purpose as the river keeps asking, why?

By the time the act approaches its break, the promise of legacy has sprung a leak. Two boats are lost, and a few of the men begin to wonder if history is worth dying wet and hungry for. The idea that someone gets to “tell the story” begins to feel dangerous. Intermission arrives precisely when it should—right as you want to beg the characters to reconsider. (They will not.)

Men on Boats is funny, incisive, and deeply theatrical. It dismantles the mythology of American exploration without flattening its characters into symbols. Instead, it lets ego, fear, and entitlement do the work. The audience is left to consider who survives, who gets remembered, and how unreliable history becomes once someone decides they were first.

(The river, of course, remembers everything.)

WHEN: January 23, 2026 - February 8, 2026

WHERE: 1210 E Main St #300, Allen TX

WEB: allencontemporarytheatre.net